Category: personal

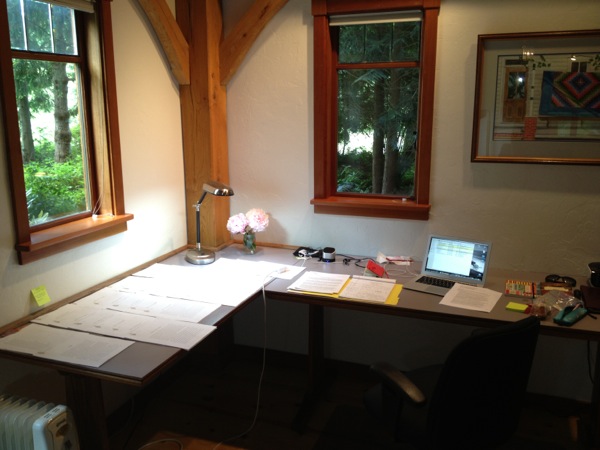

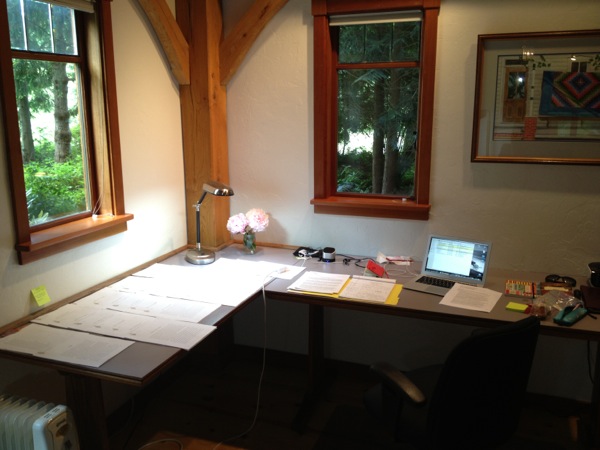

I spent the last two weeks of June at Hedgebrook, a women writer’s retreat on Whidbey Island in Washington. In a happy coincidence, I received my editorial letter just as I arrived in Oak Cottage (pictured above), so I was able to make revisions for my new novel while I was there. I loved being in residency—being alone all day, in silence, in a space where I could spread out my manuscript and all my notes was incredibly beneficial.

Now I’ve returned to my ordinary life, made more hectic by a house move, and I miss the silence.

How do you get ideas for your novels? This question, or some version of it, comes up at nearly every reading I give. Since the answer this time around is a little unusual, I thought I’d share it with you.

In the fall of 2009, I was working on an essay for The Nation magazine about Christopher Caldwell’s polemic on Muslim immigration, Reflections on the Revolution in Europe. As part of my research for the essay, I picked up Anouar Majid’s We Are All Moors, which places recent Muslim immigration in the context of a larger debate around Muslim presence in Europe, a debate that started before the expulsion of Moriscos (Spaniards of Muslim descent) from Spain in 1609.

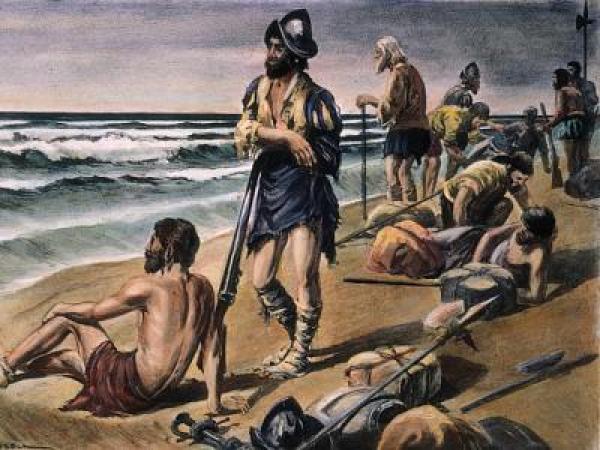

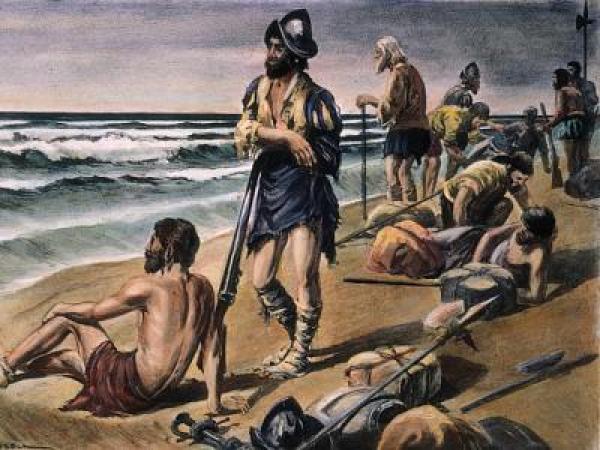

Halfway through We Are All Moors, I came across a brief mention of a certain Estebanico, a Moroccan slave who was said to be a companion of the explorer Cabeza de Vaca. The story of Alvar Nuñez Cabeza de Vaca is well known. In 1527, he and several hundred Spaniards landed in Florida as part of the Narváez expedition. The conquistadors were looking for gold, but within a year they became lost in the unfamiliar continent and only four of them survived. Cabeza de Vaca and the other survivors traveled across America, living with Indian tribes for many years. But I had not known about Estebanico, the Moroccan slave.

Why haven’t I heard of him, I wondered. Who was he? What was his real name? How did he end up in this expedition? So I read Cabeza de Vaca’s Chronicle of the Narváez Expedition, and was immediately struck by this narrative, by what it emphasized and what it left out. I decided I wanted to write Estebanico’s version of this famed journey. It is now almost four years later, and I am thrilled to report that The Moor’s Account will be published by Pantheon in 2014. I will, of course, have more updates about the book as the publication date draws near.

Image: Alfred Russell, Alvar Nuñez Cabeza de Vaca and His Companions Lost on the Shore of the Gulf of Mexico, 1528. The Granger Collection. New York.

A very short break, actually, just three days in Joshua Tree National Park. But, oh, they were glorious.

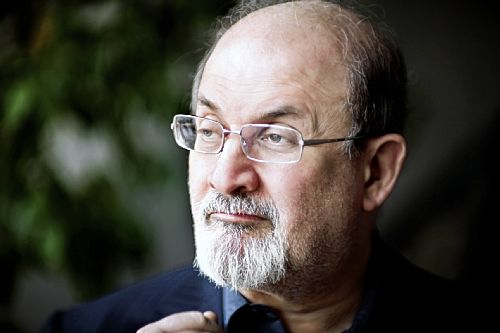

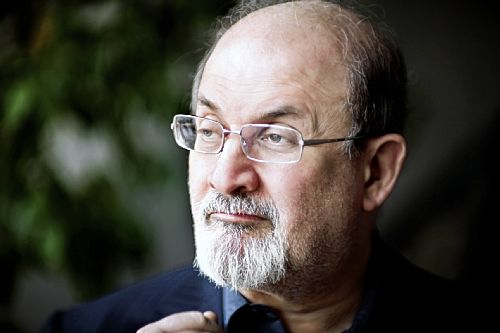

The latest issue of The Nation magazine includes an essay I wrote about Salman Rushdie’s Joseph Anton, his memoir of life during the years of the fatwa. More generally, this piece is about how society reacts to blasphemy and what those reactions tell us. Here’s how the essay starts:

The name Salman Rushdie and the word fatwa entered my vocabulary on the same February day in 1989. I was standing in the living room of my parents’ house in Morocco; my uncle, a newspaper rolled under one arm, had just arrived for dinner; my grandmother was sitting on the orange divan, her prayer beads wound on her right hand. Then someone pointed to the television screen and we all turned to look. Young men in the small British city of Bradford were burning copies of a book; the footage was interwoven with photographs of a hunched and dour-looking Khomeini. The ayatollah had found something offensive about a novel—wait, what was it called? Satanic something?—and had decreed that Muslims everywhere were duty-bound to kill its author.

Enter: Rushdie, fatwa.

As it happened, my entire family was Muslim. But to the ayatollah’s chagrin, no one rushed out to find the novelist. We ate dinner and talked about inflation and gas prices. I had grown up in a secular family, but as a teenager I had discovered religion and become a practicing Muslim. Of all those seated around our dinner table that night, the two who would have paid the most attention to a supposed insult against Islam were my grandmother and me. But my grandmother was illiterate and had wisely chosen not to form an opinion on something she had not read. And I loved books more than anything; I could not conceive of burning them.

You can read the rest here. And you can subscribe to the Nation magazine here.

(Photo credit: Syrie Moskowitz)

The end of the year is traditionally a time of retrospectives and resolutions, a ritual which I tend to resist, but with the end of my sabbatical and my imminent return to teaching, a bit of stock-taking seems inevitable. I was away from the University of California for a little over six months, which sounds like a very long leave of absence, but of course it went by in a blink. I’ve used the time to work on my new book, especially during my Lannan Foundation residency in Marfa, and I’m happy to report that I made significant progress. This novel is much longer than I anticipated when I started it three years ago and certainly the most ambitious project I’ve ever undertaken, but also the most pleasurable writing experience I’ve ever had.

This year, I also wrote a few other things here and there: a short piece for the New York Times on Ann Patchett’s State of Wonder; a review for The Nation of Percival Everett’s Assumption; an essay, also for The Nation, on Katherine Boo’s National Book Award-winning Behind the Beautiful Forevers; and contributions to the Guardian about the Arab revolutions; the Daily Beast on the rape of Amina Filali; The Nation on Islamophobia; and Newsweek on Los Angeles and a return to Morocco.

Most of the reading I’ve done in 2012 was related in some way to my novel, but I’ve also used the time to read for leisure: Joan Didion’s Run River, Leslie Marmon Silko’s Ceremony, and V.S. Naipaul’s Miguel Street were particular favorites. I read relatively few books published this year, but those that stand out were G. Willow Wilson’s Alif the Unseen, Zadie Smith’s NW, and Salman Rushdie’s Joseph Anton (about which I have an essay coming out soon.) I also read and admired Michael Gorra’s Portrait of a Novel, which tells the story of Henry James’s best-known work. This is not a traditional biography; instead, it shows us the writer at work on a single book: how he came to write it, how it relates to other books of the period, and how it was revised many years later.

I have no resolutions for 2013, save for the usual: to write, to read and learn, and to get better at what I do.

I have been back at home in Santa Monica for a few days now, but I feel as though I’m still under the spell of the magical time I spent in Marfa. I brought back a kind of energy that still surrounds and propels me, and I wonder if it has something to do with the size of the place. All my life, I’ve lived in big cities: Rabat, London, Los Angeles. But Marfa is a small town in west Texas, with a population of 2,100. Although the Lannan Foundation had graciously lent me a car for the duration of my stay, I walked everywhere I needed to go, whether to the post office, the bookstore or the farmer’s market. Everyone waved hello; everyone was friendly; everyone invited me to the Friday night football game; and everyone was a little mystified that writers go on these things called ‘residencies.’

I did attend Marfa High School’s friday night game. There were only six players on each team, instead of eleven, but the stadium lights shone just as bright. Six-man football, I was told, was the only variant that could be played in such a small town. The Marfa Shorthorns did very well that night, beating the Sanderson Eagles with a score of 55-42. But I was no closer to understanding or even really enjoying the game. (Like all Moroccans, I remain a fan of good old football, played with a round black-and-white ball.) What I enjoyed instead was watching an entire community come together to cheer and support its children.

Above is a picture of my desk. This is where I spent the better part of my time last month, working on my novel. I listened to classical music—Brahms and Rachmaninov were favorites—but I did not mind the unusual sounds of an unfamiliar place. Freight trains, which run through the center of Marfa, blew their horns several times during the day. A murder of crows roosting on the tree in the front yard kept me company in the afternoon. There were also neighborhood dogs. None of them were tethered, and I had to overcome my fear of small canines whenever I stepped out. But I loved, especially, the wild and fearless turkey who visited me from time to time. Maybe it was all this unfamiliarity that gave birth to the energy I brought back with me to the metropolis.