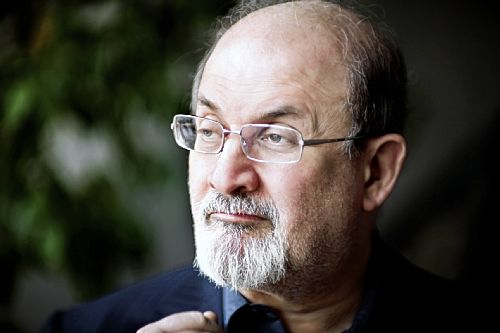

Among the Blasphemers

The latest issue of The Nation magazine includes an essay I wrote about Salman Rushdie’s Joseph Anton, his memoir of life during the years of the fatwa. More generally, this piece is about how society reacts to blasphemy and what those reactions tell us. Here’s how the essay starts:

The name Salman Rushdie and the word fatwa entered my vocabulary on the same February day in 1989. I was standing in the living room of my parents’ house in Morocco; my uncle, a newspaper rolled under one arm, had just arrived for dinner; my grandmother was sitting on the orange divan, her prayer beads wound on her right hand. Then someone pointed to the television screen and we all turned to look. Young men in the small British city of Bradford were burning copies of a book; the footage was interwoven with photographs of a hunched and dour-looking Khomeini. The ayatollah had found something offensive about a novel—wait, what was it called? Satanic something?—and had decreed that Muslims everywhere were duty-bound to kill its author.

Enter: Rushdie, fatwa.

As it happened, my entire family was Muslim. But to the ayatollah’s chagrin, no one rushed out to find the novelist. We ate dinner and talked about inflation and gas prices. I had grown up in a secular family, but as a teenager I had discovered religion and become a practicing Muslim. Of all those seated around our dinner table that night, the two who would have paid the most attention to a supposed insult against Islam were my grandmother and me. But my grandmother was illiterate and had wisely chosen not to form an opinion on something she had not read. And I loved books more than anything; I could not conceive of burning them.

You can read the rest here. And you can subscribe to the Nation magazine here.

(Photo credit: Syrie Moskowitz)