News

I mentioned last week that I was teaching Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye, so I thought I’d share a very short passage that I’ve always liked, because of how the author explores the idea of beauty in physical surroundings and then connects it to the stories we tell ourselves:

There is nothing more to say about the furnishings. They were anything but describable, having been conceived, manufactured, shipped, and sold in various states of thoughtlessness, greed and indifference. The furniture had aged without ever becoming familiar. People had owned it, but never known it. No one had lost a penny or a brooch under the cushions of either sofa and remembered the place and time of the loss or the finding. No one had clucked and said, “But I had it just a minute ago. I was sitting right there talking to . . .” or “Here it is. It must have slipped down while I was feeding the baby!” No one had given birth in one of the beds—or remembered with fondness the peeled paint places, because that’s what the baby, when he learned to pull himself up, used to pick loose. No thrifty child had tucked a wad of gum under the table. No happy drunk—a friend of the family, with a fat neck, unmarried, you know, but God how he eats!—had sat at the piano and played “You Are My Sunshine.” No young girl had stared at the tiny Christmas tree and remembered when she had decorated it, or wondered if that blue ball was going to hold, or if HE would ever come back to see it.

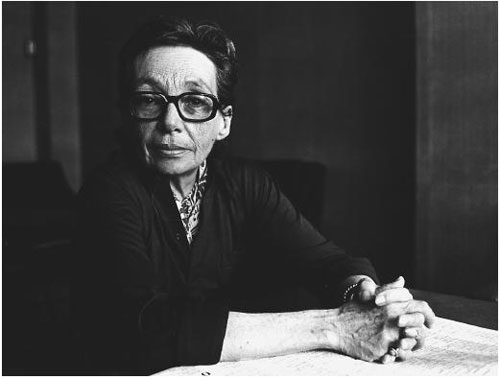

As a side note, while preparing for class, I looked up the reviews of this novel, Morrison’s first. (I do this sometimes, because I get curious about how novels that are today considered necessary or important were received when they were first published.) The NYT reviewer, one Haskel Frankel, wrote, “She reveals herself, when she shucks the fuzziness born of flights of poetic imagery, as a writer of considerable power and tenderness, someone who can cast back to the living, bleeding heart of childhood and capture it on paper. But Miss Morrison has gotten lost in her construction.” It was a decidedly mixed review, as you can see. Lucky for us that “Miss Morrison” continued to write anyway.

Photo: Toni Morrison at the Miami Book Fair in 1986.

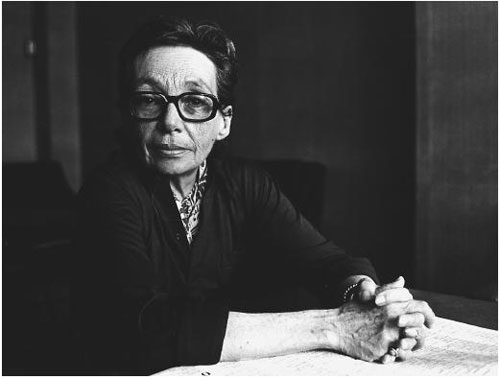

Here is a brief excerpt from Marguerite Duras’ The Lover, published in 1984:

I think it was during this journey that the image became detached, removed from all the rest. It might have existed, a photograph might have been taken, just like any other, somewhere else, in other circumstances. But it wasn’t. The subject was too slight. Who would have thought of such a thing? The photograph could only have been taken if someone could have known in advance how important it was to be in my life, that event, that crossing of the river. But while it was happening, no one even knew of its existence. Except God. And that’s why—it couldn’t have been otherwise—the image doesn’t exist. It was omitted. Forgotten. It never was detached or removed from all the rest. And it’s to this, this failure to have been created, that the image owes its virtue: the virtue of representing, of being the creator of, an absolute.

I am really intrigued by the structure of this novel, by how Marguerite Duras composed it, almost like a collage, and yet the narrative still manages to move forward smoothly. It works so beautifully to reinforce the themes of memory and forgetfulness in the the book.

Photo: Autores e Libros.

I am very happy to report that I have a short story in the newest edition of the journal Callaloo. This special issue was devoted to the Middle East and North Africa and was edited by the novelist Salar Abdoh. It includes poetry by Mahmoud Darwish, Hayan Charara, Nathalie Handal, Fady Joudah, Sholeh Wolpe; nonfiction by D.H. Melhem; fiction by Raja Alem, Ibrahim Al-Koni, Radwa Ashour, Pauline Kaldas, and yours truly. There are also photographs, art, book reviews, and drama selections. You can view the entire table of contents here. The journal is now in its 34th year, and though it was founded at the University of Louisiana at Baton Rouge, it is now primarily supported by Texas A&M University. It is an important forum of African diaspora and African-American arts and culture, and you can support it by subscribing here.

Last Friday, the New York Times ran a story about skin-whitening creams, which contain harmful steroids, but are nonetheless widely available on the market. Of course, the marketing material for these creams doesn’t use words like “whitening.” Instead, a range of euphemisms is preferred, particularly in the United States—euphemisms such as “brightening” and “clearing” and “evening out.” But when I visited Asia and certainly in places like Morocco, I’ve seen these creams advertised with the more blunt term of “whitening.” One was called “White Perfect.” The article has a pretty shocking photo montage of baseball player Sammy Sosa, before and after treatment.

All this reminded me of Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye, which I am teaching this term in one of my classes. The book is a meditation on aesthetics, beauty, and the pervasiveness of a “white aesthetic,” in which white skin equals beauty and black skin does not. It’s also a deep look at what this type of uniformly available aesthetic does to the psyche of the little girl Pecola. One of the reasons I quite like this book is that it is frank and fearless in its exploration of aesthetic preferences, something that is often, whether consciously or unconsciously, silenced in literature.

(Image source: Fun with Dick and Jane.)

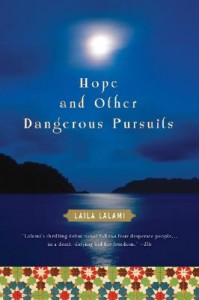

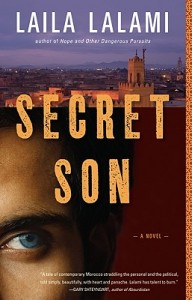

I’m happy to announce that both of my books, Hope and Other Dangerous Pursuits and Secret Son, are now available in audio format from Audible. They are narrated by the Palestinian-American actress Lameece Issaq. You can buy the CDs directly from Audible, or from Amazon (here and here).