Category: literary life

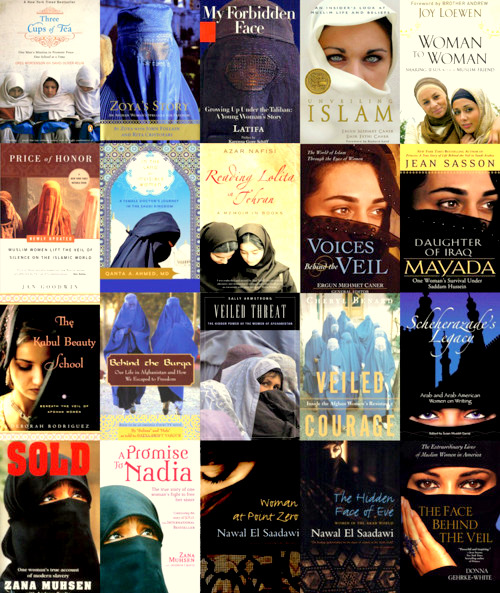

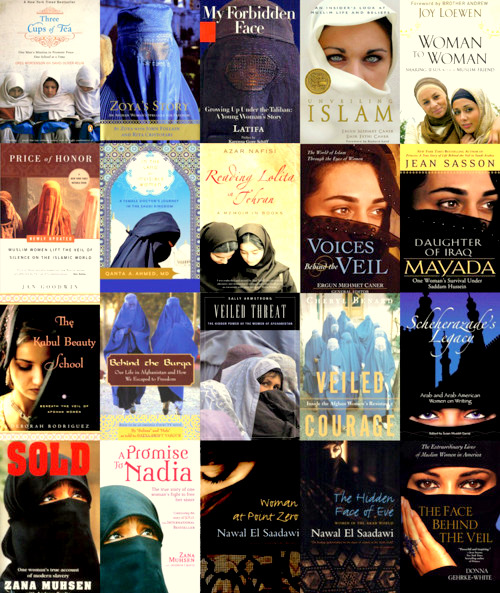

I have a new piece in The Los Angeles Review of Books about the ways in which Muslim women’s rights are discussed in different parts of the world. Here’s a snippet:

I was struck then, and I suppose I still am now, by how different the Chronicles of the Veil™ were from the books I had read when I was growing up. Those books were written by Moroccan women and for Moroccan women; the authors explicitly critiqued the laws, cultural customs, and religious beliefs that hampered Moroccan women and prevented them from achieving full equality. But the books I encountered in America, particularly in commercial bookstores, were general, even generic, in their approach. They were often set in Afghanistan, Pakistan, or Saudi Arabia. They spoke breathlessly about “Muslim women,” a population so large and so diverse that hardly any statements made about them bear scrutiny. What could possibly be said to be true of 800 million women, spread out over 56 countries, dozens of ethnic groups, and a multitude of legal and cultural practices?

There came a moment when I realized that there are two distinct kinds of conversations taking place around Muslim women — one in Muslim countries and one in Western countries. The first conversation is highly specific, and focuses on local problems. In Morocco, for example, feminist activists pushed for a reform of family law for more than a decade; it was finally passed by parliament in 2004, and it granted women greater rights in marriage, divorce, and custody. These activists also successfully lobbied parliament for another reform, this time of the penal code, because it contained a loophole that allowed a man to escape statutory rape charges in case of marriage. Now feminists are focusing on access to education in rural areas, the practice of hiring underage girls as domestic workers, sexual harassment on the street — these are issues that Moroccan women and girls face every day, but they might not be exactly the same issues faced by women in Somalia or Comoros, where the legal apparatus and cultural practices are quite different.

The second kind of conversation takes place in Western countries, primarily via the Chronicles of the Veil™ and other sensationalistic materials. Here, the terms of the debate are global.

You can read the rest of the essay here.

(Photo credit: ArabGlot)

For the last four years, I’ve spent the majority of my time inside a man’s body and mind. My character, a Moroccan slave known only as Estebanico of Azemmur, was part of a sixteenth-century Spanish expedition to claim the territory of Florida for the Crown of Castile. But the expedition turned out to be an unmitigated disaster and, within a few months, only four men were left standing: three noblemen, among whom the famed explorer Cabeza de Vaca, and Estebanico. I’ve followed along as Estebanico and the others journeyed to the heart of Florida and, desperate to survive among the Indians, reinvented themselves as faith healers. But my time with Estebanico is coming to an end. I’m happy to report that the release date for The Moor’s Account has been set for September 2014. I’m so proud of this book and so excited to share it with readers.

Illustration: Azaamurum. 1678 map of Azemmur by Daniel Meisner.

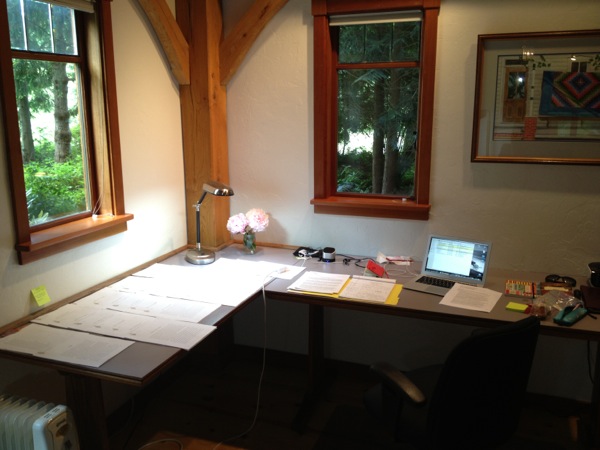

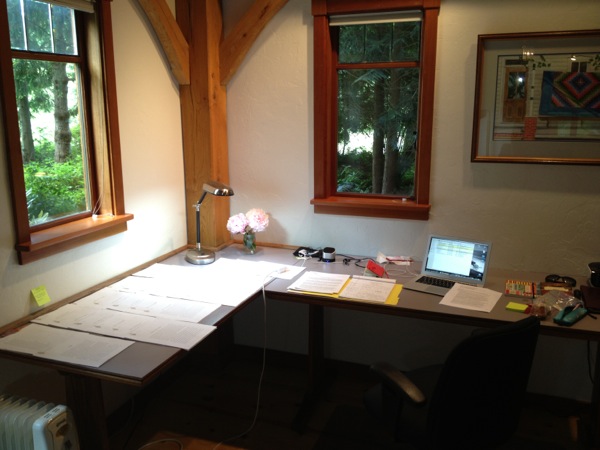

I spent the last two weeks of June at Hedgebrook, a women writer’s retreat on Whidbey Island in Washington. In a happy coincidence, I received my editorial letter just as I arrived in Oak Cottage (pictured above), so I was able to make revisions for my new novel while I was there. I loved being in residency—being alone all day, in silence, in a space where I could spread out my manuscript and all my notes was incredibly beneficial.

Now I’ve returned to my ordinary life, made more hectic by a house move, and I miss the silence.

I have been back at home in Santa Monica for a few days now, but I feel as though I’m still under the spell of the magical time I spent in Marfa. I brought back a kind of energy that still surrounds and propels me, and I wonder if it has something to do with the size of the place. All my life, I’ve lived in big cities: Rabat, London, Los Angeles. But Marfa is a small town in west Texas, with a population of 2,100. Although the Lannan Foundation had graciously lent me a car for the duration of my stay, I walked everywhere I needed to go, whether to the post office, the bookstore or the farmer’s market. Everyone waved hello; everyone was friendly; everyone invited me to the Friday night football game; and everyone was a little mystified that writers go on these things called ‘residencies.’

I did attend Marfa High School’s friday night game. There were only six players on each team, instead of eleven, but the stadium lights shone just as bright. Six-man football, I was told, was the only variant that could be played in such a small town. The Marfa Shorthorns did very well that night, beating the Sanderson Eagles with a score of 55-42. But I was no closer to understanding or even really enjoying the game. (Like all Moroccans, I remain a fan of good old football, played with a round black-and-white ball.) What I enjoyed instead was watching an entire community come together to cheer and support its children.

Above is a picture of my desk. This is where I spent the better part of my time last month, working on my novel. I listened to classical music—Brahms and Rachmaninov were favorites—but I did not mind the unusual sounds of an unfamiliar place. Freight trains, which run through the center of Marfa, blew their horns several times during the day. A murder of crows roosting on the tree in the front yard kept me company in the afternoon. There were also neighborhood dogs. None of them were tethered, and I had to overcome my fear of small canines whenever I stepped out. But I loved, especially, the wild and fearless turkey who visited me from time to time. Maybe it was all this unfamiliarity that gave birth to the energy I brought back with me to the metropolis.

The most recent issue of Newsweek includes a piece I wrote about the city of Los Angeles. Here’s how it starts:

I came to Los Angeles with a suitcase full of books and shoulder pads stuffed with cash. It was 1992, just a few months after the infamous riots, and I was about to start graduate school at the University of Southern California, near the epicenter of the unrest. One of my professors advised me against coming here—I don’t remember exactly what he said, but the substance of his message could be summarized in three words: Drugs! Guns! Violence! I had been warned so often about muggings that I decided to sew some bills inside the shoulder pads of my jacket. I didn’t know a single soul here.

You can read the rest of the piece on the website of Newsweek.

(Photo credit: Garry Winogrand, Los Angeles International Airport, 1964)

On April 16, the Pulitzer Prize Board announced that there were three finalists for the award in fiction, but no winner—a decision that sparked an outcry in some parts of the literary community. The three finalists were The Pale King, by David Foster Wallace; Swamplandia! by Karen Russell; and Train Dreams, by Denis Johnson. Each book had many vocal supporters, who were understandably upset at seeing their favorite be passed over—and not for another book, but for no book at all.

So the New York Times Magazine asked eight critics and writers, including me, to write about the books they would have chosen for the prize. You can read about our choices here. And you can chime in with your own here.