Category: book reviews / recommendations

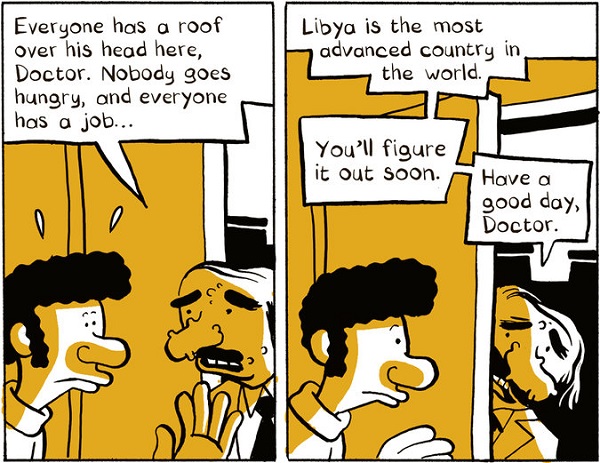

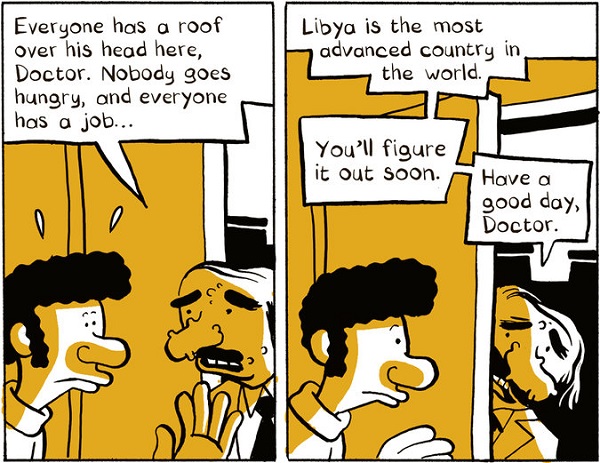

What a busy couple of weeks! I’ve been traveling, talking, and teaching almost nonstop. I’m enjoying it tremendously, but I do long for the end of the year, when things will quiet down a bit. In the meantime, I wanted to share my review of a new graphic memoir by Riad Sattouf, a former cartoonist for Charlie Hebdo. Here’s how it closes:

Already a success in France, “The Arab of the Future” will do little to complicate most people’s perceptions of Libya or Syria. Life in both countries seems like a living hell, with no moments of relief or pleasure. But this book also has occasional flashes of beauty. When Abdel-Razak comes across a mulberry tree in Tripoli, the taste of its fruit, like that of Proust’s fabled madeleine, takes him back to the carefree days of his childhood, days when the future was still full of possibility.

You can read the full review in the New York Times Book Review. Let’s see, what else? I will be on the fiction faculty at the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference in Middlebury, Vermont, next August. Register early! I am judging the PEN/Bellwether Prize, with Kathy Pories and Brando Skyhorse. Rules and eligibility are posted here. And I found out that I’ve been included in a list of the world’s 500 Most influential Muslims. I’ll raise a glass to that!

Photo credit: From The Arab of the Future via The New York Times.

My review of Mathias Énard’s novel Street of Thieves appeared in The Guardian last week. Here’s how it opens:

Tangier, Mathias Énard writes in Street of Thieves, is famous “chiefly for the people who leave it”. Take, for example, the explorer Ibn Battutah. He left Tangier in 1325 and travelled through much of Africa, the Middle East, eastern Europe and Asia. When he finally returned home, 30 years later, he wrote Rihla, an account of his adventures and one of the most important narratives we have of life in the 14th century.

Lakhdar, this novel’s 18-year-old narrator, will also leave home and write about it. Though his journeys are limited to Morocco, Tunisia and Spain, they provide a glimpse into the tremors of the Arab spring, the threat of Islamic fundamentalism, and the indignados movement in Spain. These subjects may seem ripped from the headlines, but they are not unusual for Énard, a French novelist whose work often focuses on war and political conflict.

You can read the rest here. Last week, I also spoke to NPR’s Colin Dwyer about book blurbs and why they persist. Take a look.

Photo: Bruno d’Amicis for The Guardian.

In trying to make sense of the injustice and the violence that has been unfolding in Ferguson for the last couple of weeks, I returned to James Baldwin’s essay “Notes of a Native Son,” and recommended it for NPR’s All Things Considered.

It is early August. A black man is shot by a white policeman. And the effect on the community is of “a lit match in a tin of gasoline.” No, this is not Ferguson, Mo. This was Harlem in August 1943, a period that James Baldwin writes about in the essay that gives its title to his seminal collection, Notes of a Native Son.

You can listen to the piece on NPR’s website.

Photo: Robert Cohen/St. Louis Post-Dispatch/AP. A demonstrator throws back a tear gas container after tactical officers worked to break up a group of bystanders on Chambers Road and West Florissant, Aug. 13, 2014, in St. Louis.

Happy 2014! My winter holiday was brief (as are all holidays, I suppose) and now I am back at work. For those who may be interested, my review of Hooman Majd’s The Ministry of Guidance Invites You to Not Stay appeared in the New York Times last week. Here is how it begins:

To write about one’s country while living in another is to invite questions about loyalty. Why are you writing this? And for whom? The questions can take an ominous tone: What is your agenda? The journalist Hooman Majd faced such suspicions on one of his trips to Tehran, when an employee from the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance told him bluntly: “Just because you have an Iranian passport doesn’t mean you can come here and write whatever you want when you leave.”

It was partly in an attempt to gain a wider perspective on the country of his birth that Majd, who lives in Brooklyn, took his American wife and infant son to live in Tehran for one year. “The Ministry of Guidance Invites You to Not Stay” is a memoir of 2011, spent reconnecting with the homeland he left as a baby, when his father, then a career diplomat, was posted abroad.

You can read the rest of the review here.

Photo credit: GQ.

Few writers inspire in me as much admiration and respect as J.M. Coetzee, so I was thrilled to have an opportunity to write about his most recent novel, The Childhood of Jesus, for The Nation magazine. Here is how the piece begins:

In 1516, when he was a councilor to Henry VIII, Thomas More published a slim little novel in which he described a society starkly different from his own, a place where education is universal, religious diversity is tolerated, and private property is banned. Citizens elect their prince and can unseat him if he turns tyrannical. The state provides free healthcare for everyone, and the law is so simple that there are no lawyers. For this ideal society, More coined the term Utopia (“no place” in Greek). It sounds enlightened, doesn’t it? But here is the fine print: in Utopia, each household has two slaves, drawn from among criminals or foreign prisoners of war; the prince is always a man; atheism is frowned upon; and women and children have far fewer rights than men.

Still, what enchants about Utopia is More’s dream of an ideal society, a dream shared by poets and prophets, artists and thinkers throughout the ages. In The Republic, Plato wanted the ideal city to be run by philosopher-kings. In Candide, Voltaire situated the perfect society in El Dorado, where there are schools aplenty but no prisons. In The Communist Manifesto, Marx and Engels theorized that the future would belong to workers once they had lost their chains. Every era has its utopia. Imagine there’s no heaven; it’s easy if you try.

The great J.M. Coetzee follows in this tradition in his new novel, The Childhood of Jesus, which explores the enduring question of what a just and compassionate world might look like. Over a career that has spanned forty years, the South African novelist (now an Australian citizen) has given us novels that explore the ethical responsibilities of the individual. How a person copes with power—whether political, physical or sexual—is a concern that runs through all his work. His characters often find themselves thrust into situations that force them to take note of, and act against, an injustice they had previously declined to notice. His latest novel offers a new variation on these themes: it focuses not on the drama of an unjust yet ordinary situation, but on an unusually just one.

You can read the rest of the essay here.

(Photo Credit: Basso Canarsa)

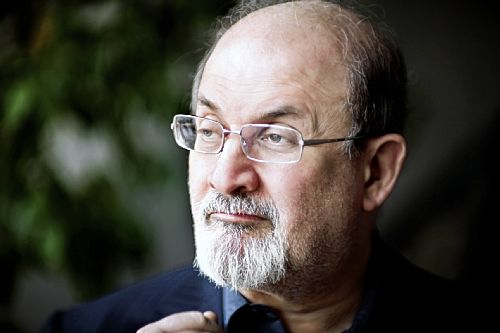

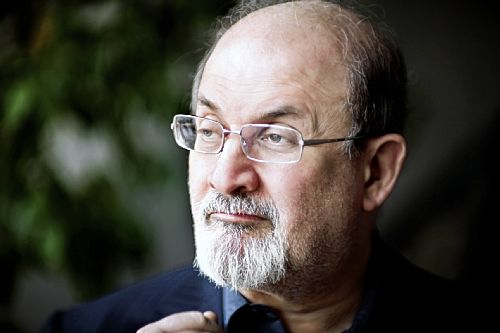

The latest issue of The Nation magazine includes an essay I wrote about Salman Rushdie’s Joseph Anton, his memoir of life during the years of the fatwa. More generally, this piece is about how society reacts to blasphemy and what those reactions tell us. Here’s how the essay starts:

The name Salman Rushdie and the word fatwa entered my vocabulary on the same February day in 1989. I was standing in the living room of my parents’ house in Morocco; my uncle, a newspaper rolled under one arm, had just arrived for dinner; my grandmother was sitting on the orange divan, her prayer beads wound on her right hand. Then someone pointed to the television screen and we all turned to look. Young men in the small British city of Bradford were burning copies of a book; the footage was interwoven with photographs of a hunched and dour-looking Khomeini. The ayatollah had found something offensive about a novel—wait, what was it called? Satanic something?—and had decreed that Muslims everywhere were duty-bound to kill its author.

Enter: Rushdie, fatwa.

As it happened, my entire family was Muslim. But to the ayatollah’s chagrin, no one rushed out to find the novelist. We ate dinner and talked about inflation and gas prices. I had grown up in a secular family, but as a teenager I had discovered religion and become a practicing Muslim. Of all those seated around our dinner table that night, the two who would have paid the most attention to a supposed insult against Islam were my grandmother and me. But my grandmother was illiterate and had wisely chosen not to form an opinion on something she had not read. And I loved books more than anything; I could not conceive of burning them.

You can read the rest here. And you can subscribe to the Nation magazine here.

(Photo credit: Syrie Moskowitz)