News

For the New York Times Magazine, I wrote about my attempts to learn more about my mother’s side of the family. Here is how the essay begins:

My mother was abandoned in a French orphanage in Fez in 1941. That year in Morocco, hundreds of people died in an outbreak of the plague; her parents were among the victims. Actually, no, they died in a horrific car crash on the newly built road from Marrakesh to Fez. No, no, no, my grandmother died in childbirth, and my grandfather, mad with grief, gave the baby away. The truth is: I don’t know how my mother ended up in a French orphanage in 1941. The nuns in black habits never told.

Growing up in Rabat, I felt lopsided, like a seesaw no one ever played with. On my father’s side: a large number of uncles, cousins, second cousins, grandaunts, all claiming descent from the Prophet Muhammad. On my mother’s side: nothing. No one. Often I imagined my mother’s parents, the man and woman whose blood pulsed in my veins but whom I had never seen.

You can read the rest of the essay here.

Illustration: “My Grandparents, Parents, and I (Family Tree)” by Frida Kahlo. Frida Kahlo Museums Trust.

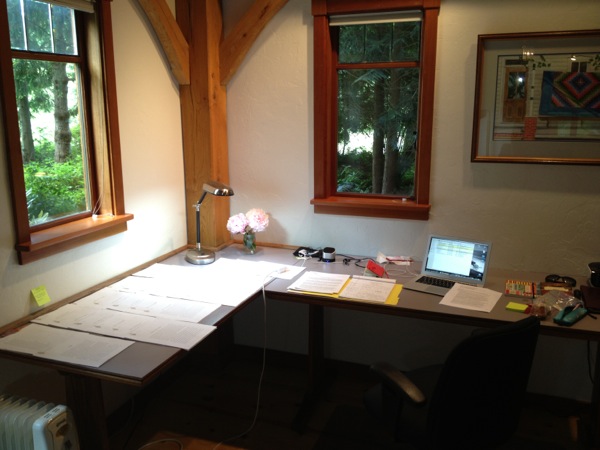

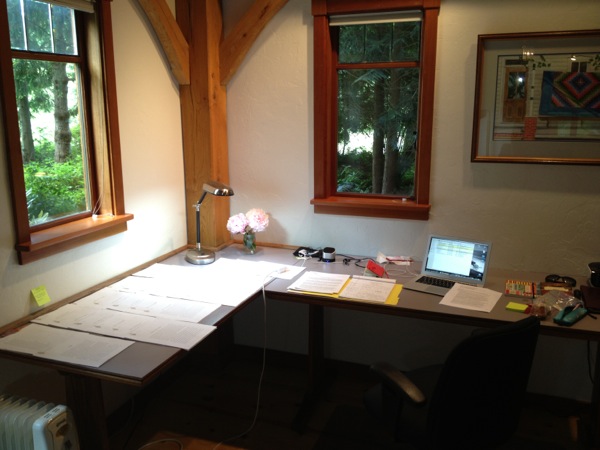

I spent the last two weeks of June at Hedgebrook, a women writer’s retreat on Whidbey Island in Washington. In a happy coincidence, I received my editorial letter just as I arrived in Oak Cottage (pictured above), so I was able to make revisions for my new novel while I was there. I loved being in residency—being alone all day, in silence, in a space where I could spread out my manuscript and all my notes was incredibly beneficial.

Now I’ve returned to my ordinary life, made more hectic by a house move, and I miss the silence.

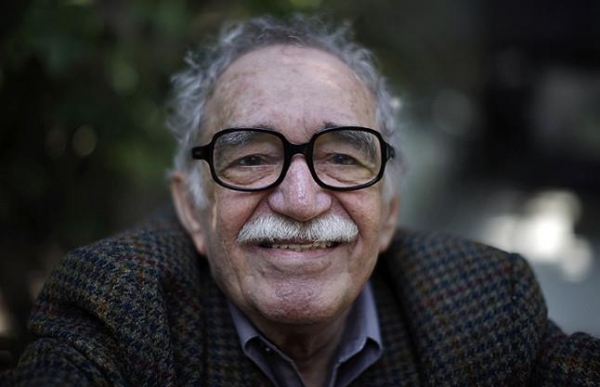

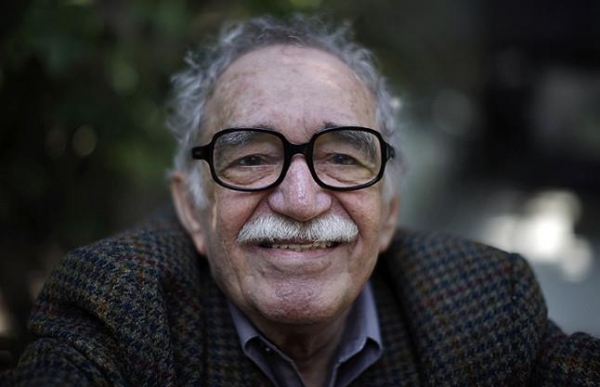

From Gabriel García Márquez’s The Autumn of the Patriarch, a stunning and mystical novel about an aging tyrant, translated from the Spanish by Gregory Rabassa:

He played endless games of dominoes with my lifetime friend General Rodrigo de Aguilar and my old friend the minister of health who were the only ones who had enough of his confidence to ask him to free a prisoner or pardon someone condemned to death, and the only ones who dared ask him to received in a special audience the beauty queen of the poor, an incredible creature from that miserable wallow we called the dogfight district because all the dogs in the neighborhood had been fighting for many years without a moment’s truce, a lethal redoubt where national guard patrols did not enter because they would be stripped naked and cars were broken up into their smallest parts with a flick of the hand, where poor stray donkeys would enter by one end of the street and come out the other in a bag of bones, they roasted the sons of the rich, general sir, they sold them in the market turned into sausages, just imagine, because Manuela Sanchez of my evil luck had been born there and lived there, a dungheap of marigold whose remarkable beauty was the astonishment of the nation general sir, and he felt so intrigued by the revelation that if all this is as true as you people say I’ll not only receive her in a special audience but I’ll dance the first waltz with her, by God, have them write it up in the newspapers, he ordered, this kind of crap makes a big hit with the poor.

My editor recommended this novel to me a few weeks ago. I am especially taken with the narration, which comes in the form of the general’s voice, but also the voices of his lieutenants and the voices of his people. It is a structure-less and plot-less wonder, one that cannot be broken down, but must be enjoyed whole, like all of Márquez work.

Photo: Miguel Tovar/AP.

How do you get ideas for your novels? This question, or some version of it, comes up at nearly every reading I give. Since the answer this time around is a little unusual, I thought I’d share it with you.

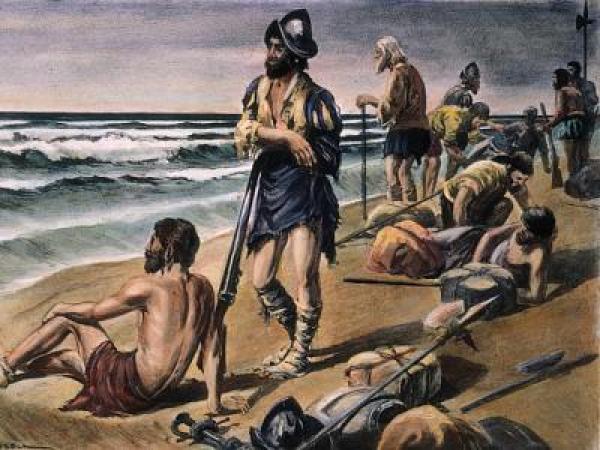

In the fall of 2009, I was working on an essay for The Nation magazine about Christopher Caldwell’s polemic on Muslim immigration, Reflections on the Revolution in Europe. As part of my research for the essay, I picked up Anouar Majid’s We Are All Moors, which places recent Muslim immigration in the context of a larger debate around Muslim presence in Europe, a debate that started before the expulsion of Moriscos (Spaniards of Muslim descent) from Spain in 1609.

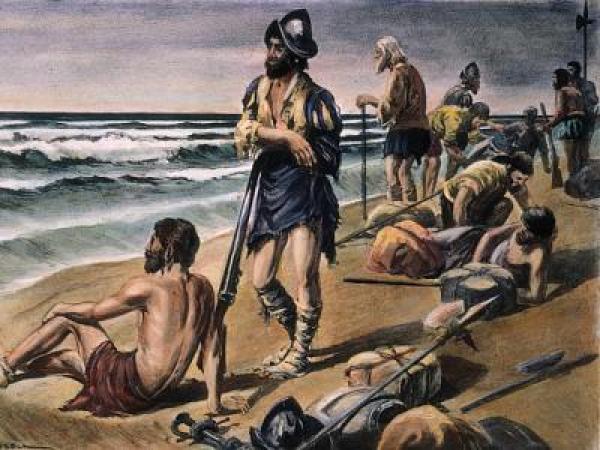

Halfway through We Are All Moors, I came across a brief mention of a certain Estebanico, a Moroccan slave who was said to be a companion of the explorer Cabeza de Vaca. The story of Alvar Nuñez Cabeza de Vaca is well known. In 1527, he and several hundred Spaniards landed in Florida as part of the Narváez expedition. The conquistadors were looking for gold, but within a year they became lost in the unfamiliar continent and only four of them survived. Cabeza de Vaca and the other survivors traveled across America, living with Indian tribes for many years. But I had not known about Estebanico, the Moroccan slave.

Why haven’t I heard of him, I wondered. Who was he? What was his real name? How did he end up in this expedition? So I read Cabeza de Vaca’s Chronicle of the Narváez Expedition, and was immediately struck by this narrative, by what it emphasized and what it left out. I decided I wanted to write Estebanico’s version of this famed journey. It is now almost four years later, and I am thrilled to report that The Moor’s Account will be published by Pantheon in 2014. I will, of course, have more updates about the book as the publication date draws near.

Image: Alfred Russell, Alvar Nuñez Cabeza de Vaca and His Companions Lost on the Shore of the Gulf of Mexico, 1528. The Granger Collection. New York.

A very short break, actually, just three days in Joshua Tree National Park. But, oh, they were glorious.