Category: quotable

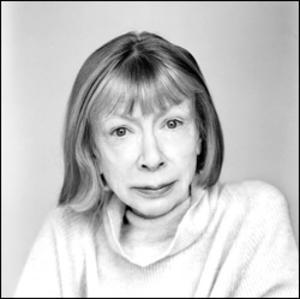

I’m working on a new essay this week, so in order to put myself in the right mood I went back to one of Joan Didion’s older essay collections, After Henry. Here is a brief excerpt from “In The Realm of the Fisher King”:

This was the world from which Nancy Reagan went in 1966 to Sacramento and in 1980 to Washington, and it is in many ways the world, although it was vanishing in situ even before Ronald Reagan was elected governor of California, she never left. My Turn did not document a life radically altered by later experience. Eight years in Sacramento left so little imprint on Mrs. Reagan that she described the house in which she lived—a house located on 45th Street off M Street in a city laid out on a numerical and alphabetical grid running from 1st Street to 66th Street and from A Street to Y Street—as “an English-style country house in the suburbs.”

She did not find it unusual that this house should have been bought for and rented to her and her husband (they paid $1,250 a month) by the same group of men who gave the State of California eleven acres on which to build the “governor’s mansion” she actually wanted and who later funded the million-dollar redecoration of the Reagan White House and who eventually bought the house on St. Cloud Road in Bel Air to which the Reagans moved when they left Washington (the street number of the St. Cloud house was 666, but the Reagans had it changed to 668 to avoid the association with the Beast in Revelations); she seemed to construe houses as part of her deal, like the housing provided to actors on location. Before the kitchen cabinet picked up by Ronald Reagan’s contract, the Reagans had lived in a house in Pacific Palisades remodeled by his then sponsor, General Electric.

I love how Didion’s sentences are structured in such a consistently effective way in all her work. I admire, for instance, the way she dislocates some of her clauses whenever she wants to save a particularly surprising or incisive point till the end. This essay originally appeared in the New York Review of Books and reprinted in After Henry, which was published in 1993.

I mentioned last week that I was teaching Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye, so I thought I’d share a very short passage that I’ve always liked, because of how the author explores the idea of beauty in physical surroundings and then connects it to the stories we tell ourselves:

There is nothing more to say about the furnishings. They were anything but describable, having been conceived, manufactured, shipped, and sold in various states of thoughtlessness, greed and indifference. The furniture had aged without ever becoming familiar. People had owned it, but never known it. No one had lost a penny or a brooch under the cushions of either sofa and remembered the place and time of the loss or the finding. No one had clucked and said, “But I had it just a minute ago. I was sitting right there talking to . . .” or “Here it is. It must have slipped down while I was feeding the baby!” No one had given birth in one of the beds—or remembered with fondness the peeled paint places, because that’s what the baby, when he learned to pull himself up, used to pick loose. No thrifty child had tucked a wad of gum under the table. No happy drunk—a friend of the family, with a fat neck, unmarried, you know, but God how he eats!—had sat at the piano and played “You Are My Sunshine.” No young girl had stared at the tiny Christmas tree and remembered when she had decorated it, or wondered if that blue ball was going to hold, or if HE would ever come back to see it.

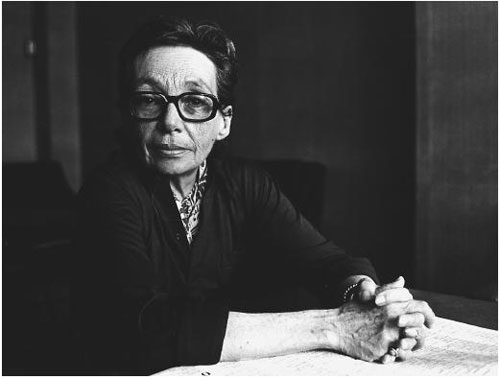

As a side note, while preparing for class, I looked up the reviews of this novel, Morrison’s first. (I do this sometimes, because I get curious about how novels that are today considered necessary or important were received when they were first published.) The NYT reviewer, one Haskel Frankel, wrote, “She reveals herself, when she shucks the fuzziness born of flights of poetic imagery, as a writer of considerable power and tenderness, someone who can cast back to the living, bleeding heart of childhood and capture it on paper. But Miss Morrison has gotten lost in her construction.” It was a decidedly mixed review, as you can see. Lucky for us that “Miss Morrison” continued to write anyway.

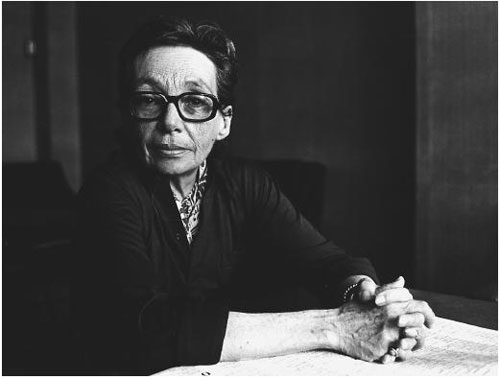

Photo: Toni Morrison at the Miami Book Fair in 1986.

Here is a brief excerpt from Marguerite Duras’ The Lover, published in 1984:

I think it was during this journey that the image became detached, removed from all the rest. It might have existed, a photograph might have been taken, just like any other, somewhere else, in other circumstances. But it wasn’t. The subject was too slight. Who would have thought of such a thing? The photograph could only have been taken if someone could have known in advance how important it was to be in my life, that event, that crossing of the river. But while it was happening, no one even knew of its existence. Except God. And that’s why—it couldn’t have been otherwise—the image doesn’t exist. It was omitted. Forgotten. It never was detached or removed from all the rest. And it’s to this, this failure to have been created, that the image owes its virtue: the virtue of representing, of being the creator of, an absolute.

I am really intrigued by the structure of this novel, by how Marguerite Duras composed it, almost like a collage, and yet the narrative still manages to move forward smoothly. It works so beautifully to reinforce the themes of memory and forgetfulness in the the book.

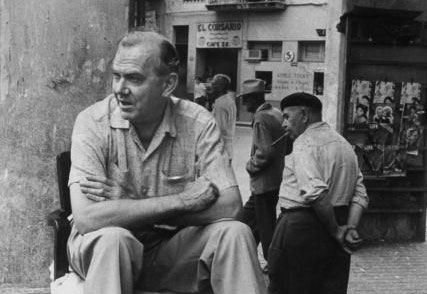

Photo: Autores e Libros.

According to a new poll by the Pew Research Center poll, 54% of Americans believe that the use of torture to gain information from suspected terrorists (note the adjective) is often or sometimes justified. This represents an increase since the last time the question was asked (49% in April and 44% in February.) Which reminds me of this passage from Graham Greene’s Our Man in Havana, where Captain Segura explains who can and can’t be tortured:

‘Did you torture him?’

Captain Segura laughed. ‘No. He doesn’t belong to the torturable class.’

‘I didn’t know there were class-distinctions in torture.’

‘Dear Mr Wormold, surely you realize there are people who expect to be tortured and others who would be outraged by the idea. One never tortures except by a kind of mutual agreement.’

‘There’s torture and torture. When they broke up Dr Hasselbacher’s laboratory they were torturing … ?’

‘One can never tell what amateurs may do. The police had no concern in that. Dr Hasselbacher does not belong to the torturable class.’

‘Who does?’

‘The poor in my own country, in any Latin American country. The poor of Central Europe and the Orient. Of course in your welfare states you have no poor, so you are untorturable. In Cuba the police can deal as harshly as they like with émigrés from Latin America and the Baltic States, but not with visitors from your country or Scandinavia. It is an instinctive matter on both sides. Catholics are more torturable than Protestants, just as they are more criminal. You see, I was right to make that king, and now I shall huff you for the last time.’

I had not realized that so many Americans subscribed to Segura’s philosophy.