Category: quotable

Last week, as the conversation on social media focused on misogyny and sexism, I kept thinking about Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale, and about this passage specifically:

Is that how we lived, then? But we lived as usual. Everyone does, most of the time. Whatever is going on is as usual. Even this is as usual, now.

We lived, as usual, by ignoring. Ignoring isn’t the same as ignorance, you have to work at it.

Nothing changes instantaneously: in a gradually heating bathtub you’d be boiled to death before you knew it. There were stories in the newspapers, of course, corpses in ditches or the woods, bludgeoned to death or mutilated, interfered with, as they used to say, but they were about other women, and them who did such things were other men. None of them were men we knew. The newspaper stories were like dreams to us, bad dreams dreamt by others. How awful, we would say, and they were, but they were awful without being believable. They were too melodramatic, they had a dimension that was not the dimension of our lives.

We were the people who were not in the papers. We lived in the blank white spaces at the edges of print. It gave us more freedom.

We lived in the gaps between the stories.

Those who think that misogyny is what happens to others are living in the gaps between the stories.

Photo: theironwriter.com

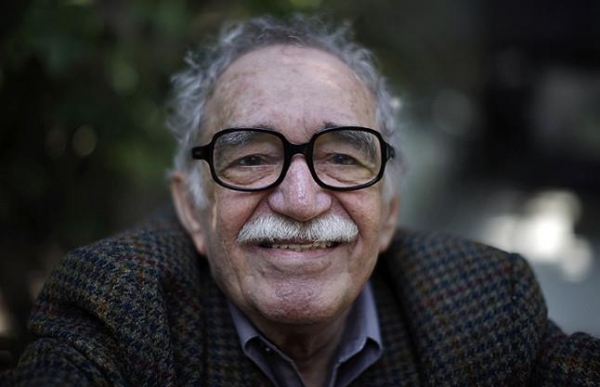

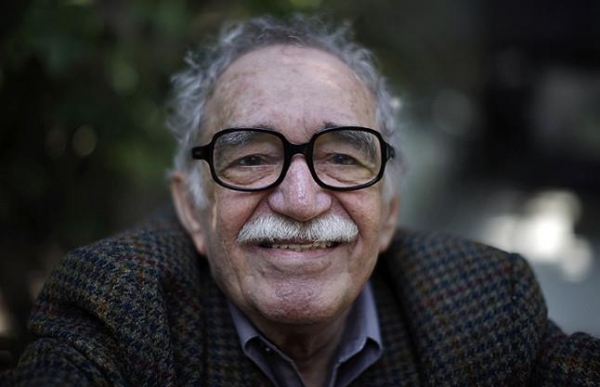

From Gabriel García Márquez’s The Autumn of the Patriarch, a stunning and mystical novel about an aging tyrant, translated from the Spanish by Gregory Rabassa:

He played endless games of dominoes with my lifetime friend General Rodrigo de Aguilar and my old friend the minister of health who were the only ones who had enough of his confidence to ask him to free a prisoner or pardon someone condemned to death, and the only ones who dared ask him to received in a special audience the beauty queen of the poor, an incredible creature from that miserable wallow we called the dogfight district because all the dogs in the neighborhood had been fighting for many years without a moment’s truce, a lethal redoubt where national guard patrols did not enter because they would be stripped naked and cars were broken up into their smallest parts with a flick of the hand, where poor stray donkeys would enter by one end of the street and come out the other in a bag of bones, they roasted the sons of the rich, general sir, they sold them in the market turned into sausages, just imagine, because Manuela Sanchez of my evil luck had been born there and lived there, a dungheap of marigold whose remarkable beauty was the astonishment of the nation general sir, and he felt so intrigued by the revelation that if all this is as true as you people say I’ll not only receive her in a special audience but I’ll dance the first waltz with her, by God, have them write it up in the newspapers, he ordered, this kind of crap makes a big hit with the poor.

My editor recommended this novel to me a few weeks ago. I am especially taken with the narration, which comes in the form of the general’s voice, but also the voices of his lieutenants and the voices of his people. It is a structure-less and plot-less wonder, one that cannot be broken down, but must be enjoyed whole, like all of Márquez work.

Photo: Miguel Tovar/AP.

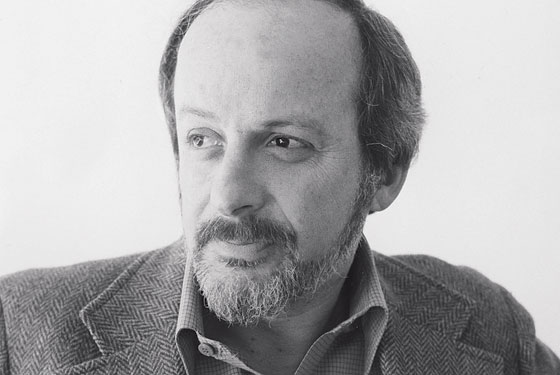

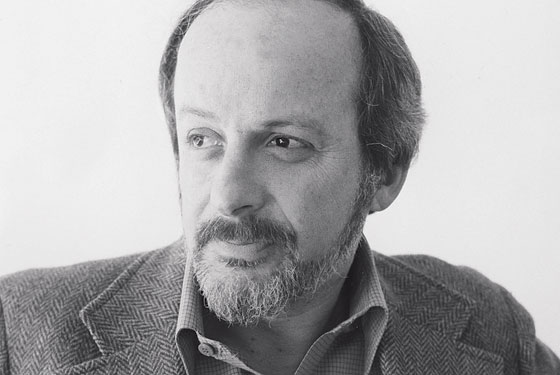

I had just finished my fiction workshop last week when I learned that Christopher Dorner, the former LAPD officer who was sought in connection with the murder and attempted murder of fellow officers, had been found. In Los Angeles that week, Dorner was the subject of intense debate, especially after the release of his manifesto, in which he alleged that the LAPD used excessive force during arrests and that he’d been fired when he reported it. Although the LAPD denied the use of excessive force, its claim was undermined by the fact that officers opened fire on a mother and daughter who were delivering newspapers, and on one man who was on his way to surf. Dorner was eventually found in a cabin in Big Bear, leading to a stand off during which he took his own life and/or was burned to death, depending on whom you believe.

The Dorner saga made me think about Coalhouse Walker, the pianist in E.L. Doctorow’s Ragtime. After a group of firemen vandalize his car, Walker seeks revenge by bombing fire stations in and around the town of New Rochelle. He sends letters to newspapers that read, “I want the fire chief turned over to my justice.” Like Dorner, Walker is the target of a statewide manhunt and a subject of curiosity and speculation.

It was widely reported when he was achieving his notoriety that Coalhouse Walker had never exhausted the peaceful and legal means of redress before taking the law in his own hands. This is not entirely true. He went to see three different attorneys recommended by Father. In all cases they refused to represent him. He was advised to recover his automobile before it was totally wrecked and to forget the matter. To all three he insisted that he didn’t want to forget the matter but to bring suit against the Fire Chief and men of the Emerald Isle Engine.

It is known too that Coalhouse made a preliminary attempt to see the matter through as his own counsel. He had filed a complaint but did not know how to go about getting a place on the court calendar or what steps had to be taken to assure that it was correct in form in order to be heard. He appeared at City Hall for an interview with the office of the County Clerk. It was suggested that he return another day when there was less pressing business in the office. But he persisted and was then told that his complaint was not on file and that several weeks would be required to trace it. Come back then, the clerk told him. Instead he went to the police station where he had originally filed and wrote out a second complaint. The policemen on duty regarded him with amazement. An older officer took him aside and confided to him that he was probably filing in vain since the volunteer fire companies were not municipal employees and therefore did not come under the jurisdiction of the city. The contemptuousness of this logic did not escape Coalhouse but he chose not to argue with it. He signed his complaint and left and heard laughter behind him as he walked out the door.

All this happened over a period of two to three weeks. Later, when the name Coalhouse Walker came to symbolize murder and arson, these earlier attempts to find redress no longer mattered. Even at this date we can’t condone the mayhem done in his cause but it is important to know the truth insofar as that is possible.

Perhaps Dorner will appear someday as a character in a novel. But, since this is Los Angeles, he’ll probably end up on film first.

Photo credit: Jerry Bauer.

From Sigrid Nunez’s The Last of Her Kind, an exquisite novel about the friendship between two women, Georgette George and Ann Drayton, who meet at Barnard in 1968. This description really doesn’t do justice to the novel, which is about many, many things: class, race, idealisms of the mind and of the heart, identity. I admired, in particular, Nunez’s ability to maintain a consistent voice for the narrator, Georgette (or Georgie, or George, as she is known at different points in her life.) Here is a taste of it:

Where I came from. Upstate: a small town way up north, near the Canadian border. Jack Frost country, winter eight months of the year. Oh, those days before the globe had warmed, what winters we had then, what snows. Drifts halfway up the telephone poles, buried fences, buried cars, roofs caving in under all that weight. Moneyless. A world of failing factories and disappearing farms, where much of the best business went to bars. People drank and drank to keep their bodies warm, their brains numb.

The people. Given the sparseness of the population, you had to ask yourself, Why so many prone to violence? Many were related, true, and a lot more closely than you liked to think. Did inbreeding lead to viciousness? Alcoholism certainly did, and alcoholism was universal. Whole families drank themselves to disgrace, to criminal mischief, to early death. Here was a place where people seemed to be forever falling. And talk about secrets–more skeletons in the closets than in the cemeteries. Statistically not a high-crime area, but a world of everyday brutality: bar brawls, battered wives. And not every misdeed was perpetrated under the influence. I remember acts of violent cruelty even among children. Woe to the weak, the smaller kids, the animals (oh, the animals) that fell in those hands. And I remember blood feuds with roots going way back to before my grandparents’ time, feuds that left at least one in every generation maimed or dead. The savage world of the North Country poor. I do not exaggerate. The boy next door, a teenage giant with a speech defect so severe only his mother could understand him, hanged a litter of kittens from the branches of the Christmas tree.

And yet for all this, as I say, I was homesick when I went away to school.

I met Nunez at the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference some years ago, when I was a fellow and she was on the faculty, but I’ve only now read this novel. A treat.

I’ve tried to avoid the trailer of the film adaptation of David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas. (I mean: the Wachowskis? Tom Hanks? Hugo Weaving as an Asian man? Huh?) But last week I gave in and watched it and now I’m curious to see it. The novel has six interweaving story lines, although ‘interweaving’ isn’t quite the right word to describe what Mitchell does: multiple voices, multiple styles, multiple genres, multiple eras, all of them held together with a fragile thread—the transmigration of souls.

The passage below, about life, death and rebirth, and which I can hardly ever re-read without having a knot in my throat, is from the Frobisher story, “Letters from Zedelghem.”

Luger here. Thirteen minutes to go. Feel trepidation, naturally, but my love of this coda is stronger. An electrical thrill that, like Adrian, I know I am to die. Pride, that I shall see it through. Certainties. Strip back the beliefs pasted on by governesses, schools and states, you find indelible truths at one’s core. Rome’ll decline and fall again. Cortés’ll lay Tenochtitlán to waste again, and later, Ewing will sail again, Adrian’ll be blown to pieces again, you and I’ll sleep under Corsican stars again, I’ll come to Bruges again, fall in and out of love with Eva again, you’ll read this letter again, the sun’ll grow cold again. Nietzsche’s gramophone record. When it ends, the Old One plays it again, for an eternity of eternities.

Time cannot permeate this sabbatical. We do not stay dead long. Once my Luger let me go, my birth, next time around, will be upon me in a heartbeat. Thirteen years from now we’ll meet again at Gresham, ten years later I’ll be back in this same room, holding this same gun, composing this same letter, my resolution as perfect as my many-headed sextet. Such elegant certainties comfort me at this quiet hour.

More on David Mitchell here.

Photo credit: The Guardian.

Earlier this week, Toni Morrison was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom at a ceremony in the White House. In his remarks, Barack Obama mentioned that he read Song of Solomon not just to learn how to write, but also “how to be.” Song of Solomon is one of my favorite of Morrison’s novels. And it struck me that it often uses repetition as a stylistic device, which is something that Obama does a lot in his speeches. So I thought I’d excerpt two short paragraphs from the book, both of which use repetition masterfully. Here is a passage from early on in the book, describing Macon Dead’s car:

In 1936 there were very few among them who lived as well as Macon Dead. Others watched the family gliding by with a tiny bit of jealousy and a whole lot of amusement, for Macon’s wide green Packard belied what they thought a car was for. He never went over twenty miles an hour, never gunned his engine, never stayed in first gear for a block or two to give pedestrians a thrill. He never had a blown tire, never ran out of gas and needed twelve grinning raggle-tailed boys to help him push it up a hill or over to a curb. No rope ever held the door to its frame, and no teenagers leaped on his running board for a lift down the street. He hailed no one and no one hailed him. There was never a sudden braking and backing up to shout or laugh with a friend. No beer bottles or ice cream cones poked from the open windows. Nor did a baby boy stand up to pee out of them. He never let rain fall on it if he could help it and he walked to Sonny’s Shop–taking the car out only on these occasions. What’s more, they doubted that he had ever taken a woman into the back seat, because rumor was that he went to “bad houses” or lay, sometimes, with a slack or lonely female tenant. Other than the bright and roving eyes of Magdalene called Lena and First Corinthians, the Packard had no real lived life at all. So they called it Macon Dead’s hearse.

The repetition of the adverb “never” obviously emphasizes how little use Macon Dead makes of the car, but it also informs us about the multiple uses other people in his community might have made of it. Halfway through, the switch from “never” to “no” highlights the fact that the car, like its owner, lacks a certain essence, a kind of vitality. All of which leads us to its funny, and appropriate, nickname: “Macon Dead’s hearse.”

Now, toward the end of the novel, Macon Dead’s son returns to Montour County to learn more about his deceased grandfather, who was also named Macon Dead. And, here, Toni Morrison uses the same device, but for the opposite effect. This is a description of the farm that the elder Macon owned:

A farm that colored their lives like a paintbrush and spoke to them like a sermon. “You see?” the farm said to them. “See? See what you can do? Never mind you can’t tell one letter from another, never mind you born a slave, never mind you lose your name, never mind your daddy dead, never mind nothing. Here, this here, is what a man can do if he puts his mind to it and his back in it. Stop sniveling,” it said. “Stop picking around the edges of the world. Take advantage, and if you can’t take advantage, take disadvantage. We live here. On this planet, in this nation, in this county right here. Nowhere else! We got a home in this rock, don’t you see! Nobody starving in my home; nobody crying in my home, and if I got a home, you got one too! Grab it. Grab this land! Take it, hold it, my brothers, make it, my brothers, shake it, squeeze it, turn it, twist it, beat it, kick it, kiss it, whip it, stomp it, dig it, plow it, seed it, reap it, rent it, buy it, sell it, own it, build it, multiply it, and pass it on–can you hear me? Pass it on!”

Though the sentence starts familiarly with the repetition of “never,” it doesn’t speak of what never happens, but of what people should never mind happening. It isn’t about absence, it’s about presence and power. And then other syntactic forms are repeated: the demonstrative (“this nation, this county”) and the imperative (“take it, hold it”), for instance, to emphasize that power. The beauty of the two passages is how, through the description of two simple possessions, the car and the farm, we get two portraits of two very different Macon Deads.

Photo credit: Mandel Ngan/AFP/Getty Images