Category: personal

In my last blog post, I talked about how I’ve been having a hard time with my new novel. I don’t like to complain about my novel–really, who needs more whining from a writer? But that week had been particularly brutal. Now, though, I’ve heard some lovely news, and I thought I’d share that with you too. I’ve been awarded a Lannan Residency Fellowship by the Lannan Foundation for next fall. What this means is that I will finally have that most precious of things: uninterrupted time to work on my book. The fellowship really could not have come at a better moment, so thank you to whoever nominated me for this!

I neglected to mention that, last month, the Guardian asked a few writers, including me, to reflect on the uprisings in the Arab world, one year later. And I also have an essay about Percival Everett’s new novel in this week’s Nation. (The article is only available to subscribers, but you can subscribe to the magazine here, for as little as $10.)

One last thing. Over the last few weeks, I’ve had to contend with several hacking attacks on my website. (As if I didn’t have enough craziness in my life.) So I’ve had to do a few upgrades to security, and I got myself a new design as well, thanks to the brilliant people at Being Wicked. If you’re looking for great web designers, hire them. They’re amazing.

I’ve just returned from Death Valley, where I went to decompress a bit after a particularly rough writing week. There’s something about the landscape there that resonates with me—it’s topographically diverse and incredibly peaceful. If you stand still for a moment, you can hear complete silence. Here is a picture of Titus Canyon early in the morning.

Farther down the trail in Titus Canyon:

Then there are the salt flats at Badwater Basin:

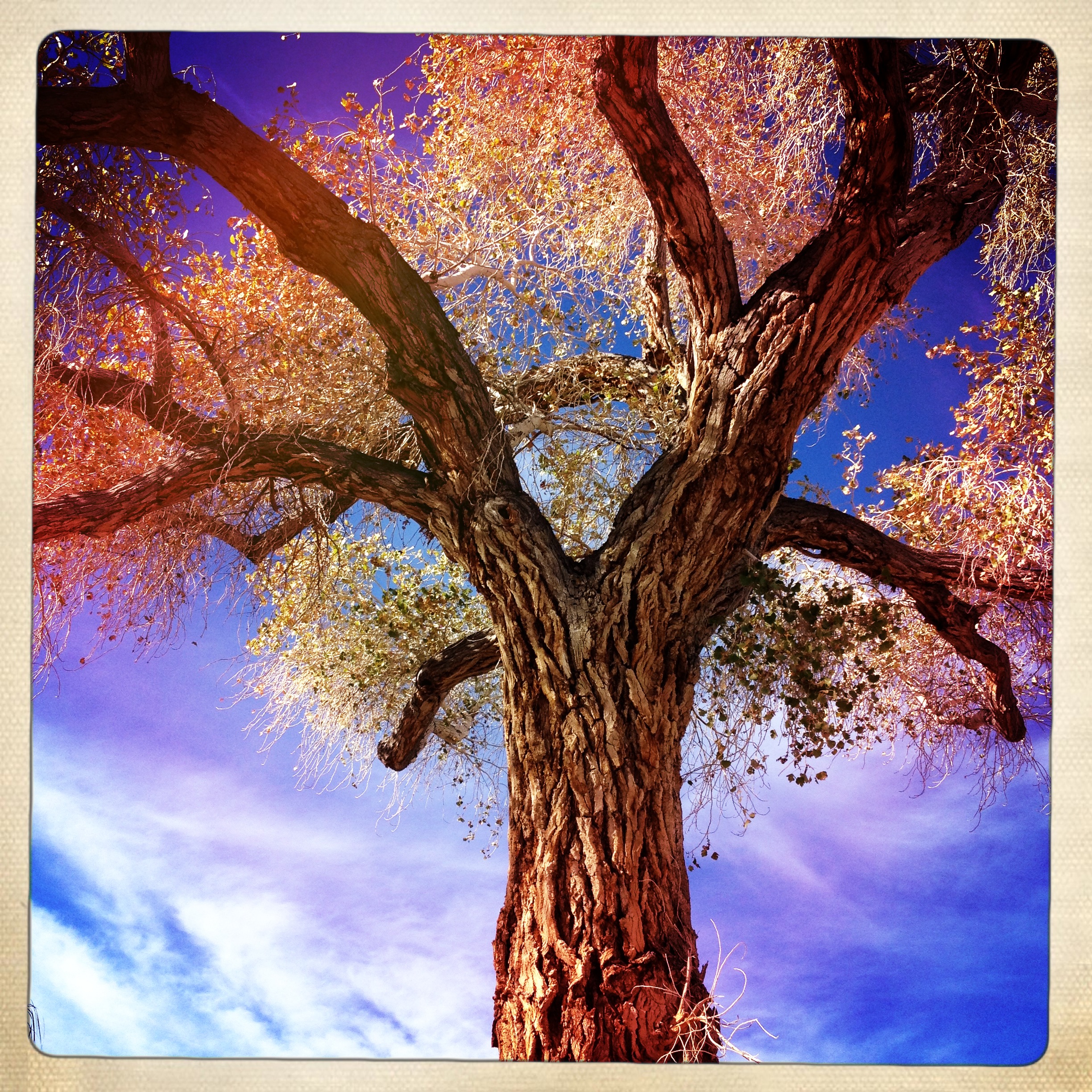

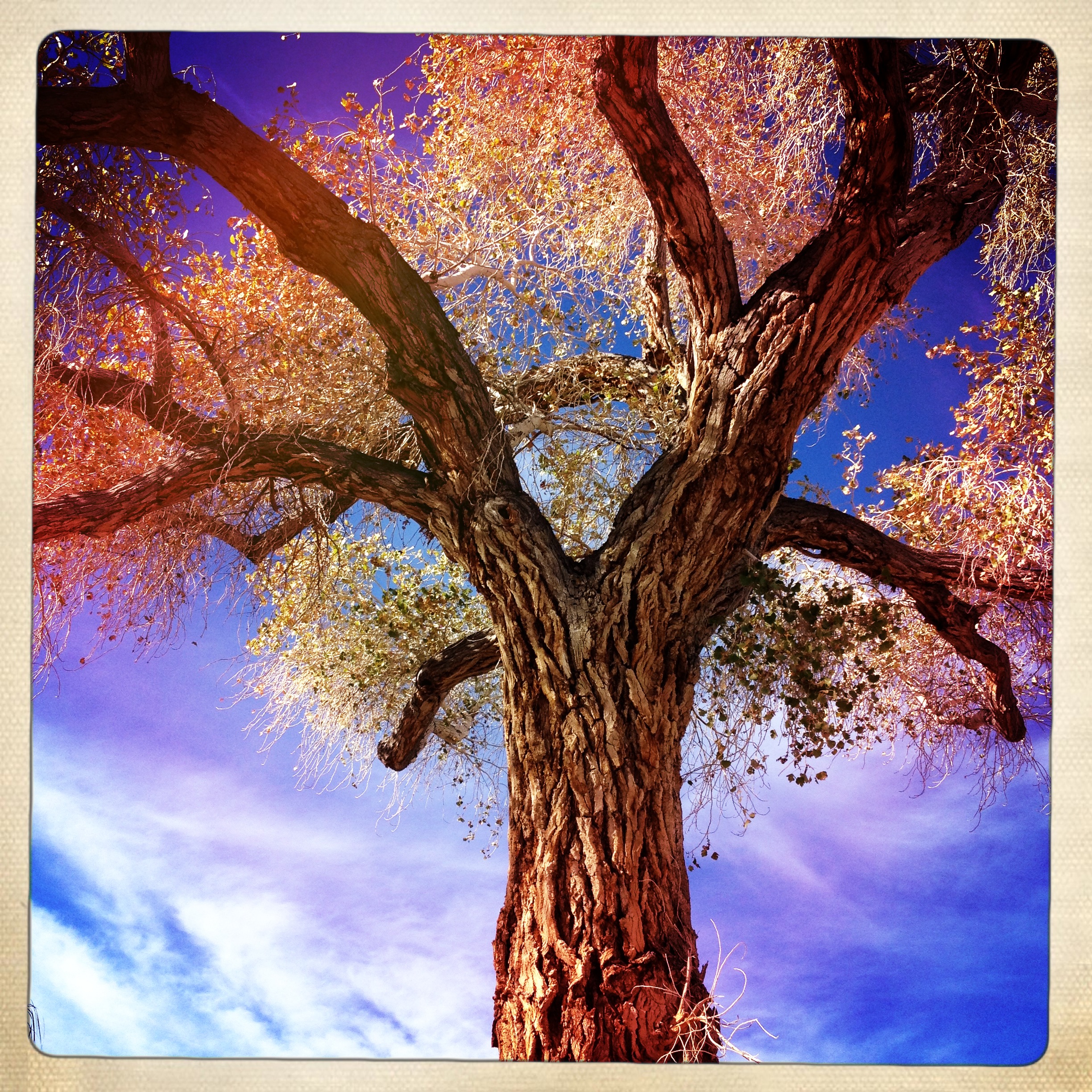

A cottonwood tree in Grapevine Canyon:

Ubehebe Crater:

And, lastly, Mustard Canyon:

There is a passage in John Cheever’s “Goodbye, My Brother” that has always haunted me. (The story, which originally appeared in The New Yorker, can be found in The Stories of John Cheever. It’s narrated by a middle-aged high school teacher, an optimistic and unreflecting man. The setting is a family home on the shore of a Massachusetts island, where the narrator’s mother and siblings get together for a summer holiday. Three of the siblings get along reasonably well, but the fourth, Lawrence, is disliked by everyone because of his pessimism. The siblings refer to him, variously, as “Tifty,” “Croaker,” and “Little Jesus.”) Near the end of the story, the narrator tries to talk Lawrence out of his gloominess:

I let him get ahead again and I walked behind him, looking at his shoulders and thinking of all the goodbyes he had made. When Father drowned, he went to church and said goodbye to Father. It was only three years later that he concluded that Mother was frivolous and said goodbye to her. In his freshman year at college, he had been good friends with his roommate, but the man drank too much, and at the beginning of the spring term Lawrence changed roommates and said goodbye to his friend. When he had been in college for two years, he concluded that the atmosphere was too sequestered and he said goodbye to Yale. He enrolled at Columbia and got his law degree there, but he found his first employer dishonest and at the end of six months he said goodbye to a good job. He married Ruth in City Hall and said goodbye to the Protestant Episcopal Church; they went to live on a back street in Tuckahoe and said goodbye to the middle class. In 1938, he went to Washington to work as a government lawyer, saying goodbye to private enterprise, but after eight months in Washington he concluded that the Roosevelt administration was sentimental and he said goodbye to it. They left Washington for a suburb of Chicago, where he said goodbye to his neighbors, one by one, on counts of drunkenness, boorishness, and stupidity. He said goodbye to Chicago and went to Kansas; he said goodbye to Cleveland and come East again, stopping at Laud’s Head long enough to say goodbye to the sea. It was elegiac and it was bigoted and narrow, it mistook circumspection for character, and I wanted to help him. “Come out of it,” I said. “Come out of it, Tifty.”

I have seemingly nothing in common with Lawrence, not even this tendency to say goodbye to everyone and everything. And yet the impulse behind his saying goodbye is one that I recognize, one that I have lived with and struggled with for many years. I think it comes from expecting so much from oneself, from others, from the world in general, which is nothing if not a guarantee of disappointment. But I also have moments when I identify with the narrator, who seems to enjoy the life he has—he swims, plays tennis, goes to a party with his wife, and generally tries to have a good time—without expecting anything else. By the end of “Goodbye, My Brother,” the narrator lashes out at Lawrence, who leaves the island. Only then does the narrator reflect:

Oh, what can you do with a man like that? What can you do? How can you dissuade his eye in a crowd from seeking out the cheek with acne, the infirm hand; how can you teach him to respond to the inestimable greatness of the race, the harsh surface beauty of life; how can you put his finger for him on the obdurate truths before which fear and horror are powerless? The sea that morning was iridescent and dark. My wife and my sister were swimming — Diana and Helen — and I saw their uncovered heads, black and gold in the dark water. I saw them come out and I saw that they were naked, unshy, beautiful and full of grace, and I watched the naked women walk out of the sea.”

One brother is consumed with obsessive rumination; the other is after constant gratification. One is given to despair; the other to hope. One lives in the past; the other in the present. Perhaps the reason I identify with both is that I see myself in both.

A couple of weeks ago, Maud Newton linked to a short list of English words Nabokov reportedly found difficult to pronounce. The diacritical marks were meant to help him remember which syllable was to receive stress:

prívet

clématis

bígoted

pólypany

múltiple

cátechism

sólace

péctoral

Botocúdos

málleable

nastúrtium

In high school, I learned English from other non-native speakers (two of them Moroccans, one a Belgian). In college, I had three British professors, but the rest were Moroccan: some spoke with a British accent, others with an American one, depending on where they had done their graduate studies. All this made for a thoroughly confusing mix of regional dialects and foreign accents. So when I moved to London to attend UCL, I was never entirely sure how to pronounce certain words, words I had come across before mostly in print, like incredulous and mandatory, or words with Greek and Latin roots, like anthropomorphic and debilitating. Then there were the baffling exceptions, like Gloucester and Leicester, which didn’t sound at all the way they were written. But eventually, my ear grew accustomed to British English. Then I arrived in Los Angeles. And, oh, the words that gave me trouble! Like delicatessen and Mississippi and coroner and a dozen others. But I always relied on mental diacritics. I never had a list like the one above—a little snapshot of personal history.

Recently, NPR’s Talk of the Nation did a series of segments on “common reads.” (These are programs in which incoming college freshmen in the U.S. are required to read the same book over the summer holiday and then discuss it in their first few classes.) Popular selections this year include The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, The Other Wes Moore, and Guns, Germs, and Steel, among others.

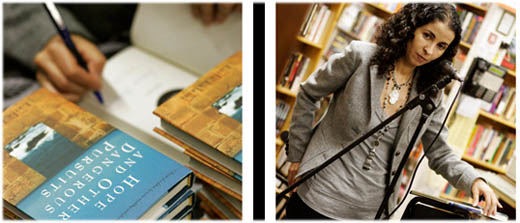

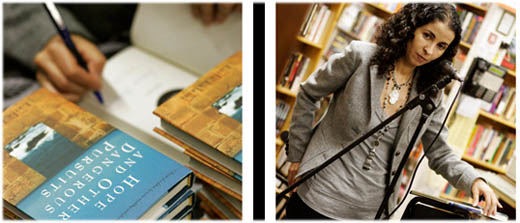

Now, I didn’t do my undergraduate studies in the United States, so I had no idea what “common readings” were until Hope and Other Dangerous Pursuits was selected for the Life of the Mind program at the University of Tennessee, back in 2006. Over the course of three days, I visited the campus, spoke to several classes, and gave a public lecture. Since then, I’ve done quite a few common readings, the most recent of which was earlier this week at Wingate University in North Carolina, where first-year students (a term I much prefer to “freshmen”) read Hope. I always find it fun to talk to younger students about the book; they always have the most interesting (and often unusual!) questions.

Photo credit: Ibarionex Perello. This was taken at a reading at the now defunct Dutton’s Books.

The weather was wonderfully hot in Santa Monica all of last week, as if to reassure me that I could hold on to summer for a little while longer. But today it’s noticeably cooler, and there is a chance of thunderstorms. The quarter at UC will be starting in just a couple of weeks. Part of me is excited about the prospect of being on campus again–there’s such a great energy the classroom. But part of me still wants to hold on to summer, and to my long days of reading and writing.

Speaking of writing, I have a short story this week in the Guardian. It’s called “Echo,” and is part of a series on 9/11 fiction that also features the work of Geoff Dyer, Kamila Shamsie, and Helon Habila. (I know that, by now, you must all be sick of hearing about 9/11 reading lists, or 9/11 photographs, or 9/11 retrospectives. But this story doesn’t even mention 9/11. Really. Have a read!)

In other news, I also received in the mail this week copies of the Granta Book of the African Short Story, where “Homecoming,” one of the stories from my collection, is reprinted. I’m amazed at how much love Hope and Other Dangerous Pursuits continues to get, even this many years after its publication. (I wish I could tell my younger self, when she was receiving rejection after rejection for that particular story, that someday its time would come.)

And if fiction isn’t really your cup of tea, you can also find me in The Nation, discussing Moroccan “exceptionalism.” For now, I have to start getting ready for fall: syllabi, reading lists, and sensible shoes.