Category: personal

L.A. readers: I will be in conversation with Dinaw Mengestu at the Los Angeles Public Library this week. The occasion is the publication of his new novel, All Our Names, about a young student from Ethiopia and a social worker from the Midwest, who take turns narrating their lives and the start of their affair. The book received a rave review in this weekend’s New York Times, and I’m really looking forward to discussing it with Dinaw. Here are the details:

Thursday, March 27

7pm

Mark Taper Auditorium-Central Library

Los Angeles Public Library

630 W. 5th Street

Los Angeles, CA 90071

(213) 228-7000

I hope to see you there.

My work appears in two wonderful anthologies that are being published this month. Dismantle collects stories and essays by alumni and teachers from the Voices of Our Nation Workshop. (VONA is a great organization that nurtures and supports writers of color.) Contributors include Chris Abani, Nikky Finney, Maaza Mengiste, Minal Hajratwala, Justin Torres, Cristina Garcia, Mat Johnson, Mitchell Jackson, and me. The book also has an introduction by Junot Díaz.

Immigrant Voices, which is edited by Achy Obejas and Megan Bayles, features the work of Aleksandar Hemon, Edwidge Danticat, Lara Vapnyar, Yiyun Li, Sefi Atta, Daniel Alarcón, Porochista Khakpour, and Junot Díaz. The anthology is released by the Great Books Foundation in Chicago. A launch party is scheduled for March 19, and you can find out more about it here.

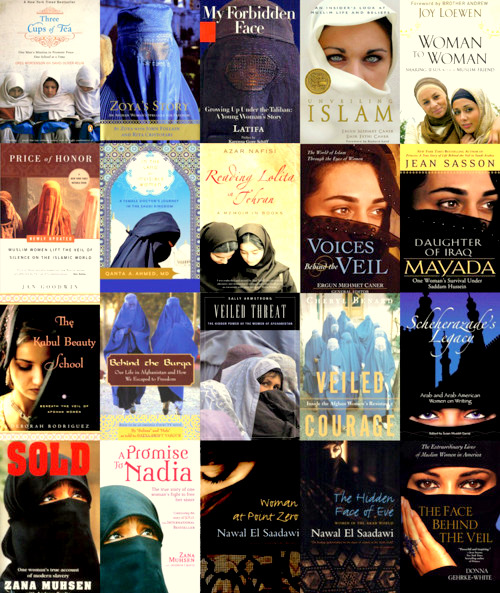

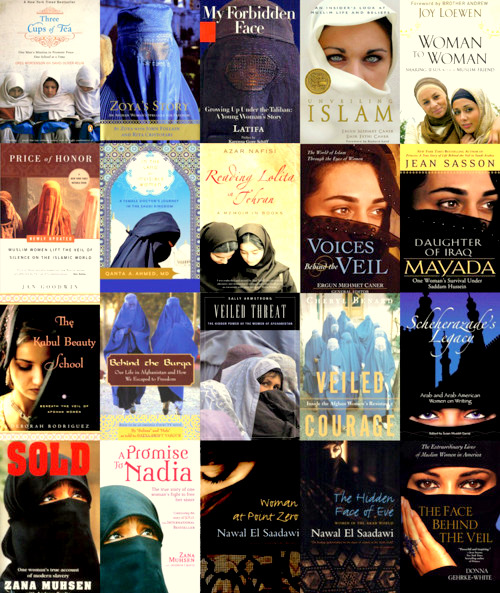

I have a new piece in The Los Angeles Review of Books about the ways in which Muslim women’s rights are discussed in different parts of the world. Here’s a snippet:

I was struck then, and I suppose I still am now, by how different the Chronicles of the Veil™ were from the books I had read when I was growing up. Those books were written by Moroccan women and for Moroccan women; the authors explicitly critiqued the laws, cultural customs, and religious beliefs that hampered Moroccan women and prevented them from achieving full equality. But the books I encountered in America, particularly in commercial bookstores, were general, even generic, in their approach. They were often set in Afghanistan, Pakistan, or Saudi Arabia. They spoke breathlessly about “Muslim women,” a population so large and so diverse that hardly any statements made about them bear scrutiny. What could possibly be said to be true of 800 million women, spread out over 56 countries, dozens of ethnic groups, and a multitude of legal and cultural practices?

There came a moment when I realized that there are two distinct kinds of conversations taking place around Muslim women — one in Muslim countries and one in Western countries. The first conversation is highly specific, and focuses on local problems. In Morocco, for example, feminist activists pushed for a reform of family law for more than a decade; it was finally passed by parliament in 2004, and it granted women greater rights in marriage, divorce, and custody. These activists also successfully lobbied parliament for another reform, this time of the penal code, because it contained a loophole that allowed a man to escape statutory rape charges in case of marriage. Now feminists are focusing on access to education in rural areas, the practice of hiring underage girls as domestic workers, sexual harassment on the street — these are issues that Moroccan women and girls face every day, but they might not be exactly the same issues faced by women in Somalia or Comoros, where the legal apparatus and cultural practices are quite different.

The second kind of conversation takes place in Western countries, primarily via the Chronicles of the Veil™ and other sensationalistic materials. Here, the terms of the debate are global.

You can read the rest of the essay here.

(Photo credit: ArabGlot)

For the last four years, I’ve spent the majority of my time inside a man’s body and mind. My character, a Moroccan slave known only as Estebanico of Azemmur, was part of a sixteenth-century Spanish expedition to claim the territory of Florida for the Crown of Castile. But the expedition turned out to be an unmitigated disaster and, within a few months, only four men were left standing: three noblemen, among whom the famed explorer Cabeza de Vaca, and Estebanico. I’ve followed along as Estebanico and the others journeyed to the heart of Florida and, desperate to survive among the Indians, reinvented themselves as faith healers. But my time with Estebanico is coming to an end. I’m happy to report that the release date for The Moor’s Account has been set for September 2014. I’m so proud of this book and so excited to share it with readers.

Illustration: Azaamurum. 1678 map of Azemmur by Daniel Meisner.

Few writers inspire in me as much admiration and respect as J.M. Coetzee, so I was thrilled to have an opportunity to write about his most recent novel, The Childhood of Jesus, for The Nation magazine. Here is how the piece begins:

In 1516, when he was a councilor to Henry VIII, Thomas More published a slim little novel in which he described a society starkly different from his own, a place where education is universal, religious diversity is tolerated, and private property is banned. Citizens elect their prince and can unseat him if he turns tyrannical. The state provides free healthcare for everyone, and the law is so simple that there are no lawyers. For this ideal society, More coined the term Utopia (“no place” in Greek). It sounds enlightened, doesn’t it? But here is the fine print: in Utopia, each household has two slaves, drawn from among criminals or foreign prisoners of war; the prince is always a man; atheism is frowned upon; and women and children have far fewer rights than men.

Still, what enchants about Utopia is More’s dream of an ideal society, a dream shared by poets and prophets, artists and thinkers throughout the ages. In The Republic, Plato wanted the ideal city to be run by philosopher-kings. In Candide, Voltaire situated the perfect society in El Dorado, where there are schools aplenty but no prisons. In The Communist Manifesto, Marx and Engels theorized that the future would belong to workers once they had lost their chains. Every era has its utopia. Imagine there’s no heaven; it’s easy if you try.

The great J.M. Coetzee follows in this tradition in his new novel, The Childhood of Jesus, which explores the enduring question of what a just and compassionate world might look like. Over a career that has spanned forty years, the South African novelist (now an Australian citizen) has given us novels that explore the ethical responsibilities of the individual. How a person copes with power—whether political, physical or sexual—is a concern that runs through all his work. His characters often find themselves thrust into situations that force them to take note of, and act against, an injustice they had previously declined to notice. His latest novel offers a new variation on these themes: it focuses not on the drama of an unjust yet ordinary situation, but on an unusually just one.

You can read the rest of the essay here.

(Photo Credit: Basso Canarsa)

For the New York Times Magazine, I wrote about my attempts to learn more about my mother’s side of the family. Here is how the essay begins:

My mother was abandoned in a French orphanage in Fez in 1941. That year in Morocco, hundreds of people died in an outbreak of the plague; her parents were among the victims. Actually, no, they died in a horrific car crash on the newly built road from Marrakesh to Fez. No, no, no, my grandmother died in childbirth, and my grandfather, mad with grief, gave the baby away. The truth is: I don’t know how my mother ended up in a French orphanage in 1941. The nuns in black habits never told.

Growing up in Rabat, I felt lopsided, like a seesaw no one ever played with. On my father’s side: a large number of uncles, cousins, second cousins, grandaunts, all claiming descent from the Prophet Muhammad. On my mother’s side: nothing. No one. Often I imagined my mother’s parents, the man and woman whose blood pulsed in my veins but whom I had never seen.

You can read the rest of the essay here.

Illustration: “My Grandparents, Parents, and I (Family Tree)” by Frida Kahlo. Frida Kahlo Museums Trust.