Category: literary life

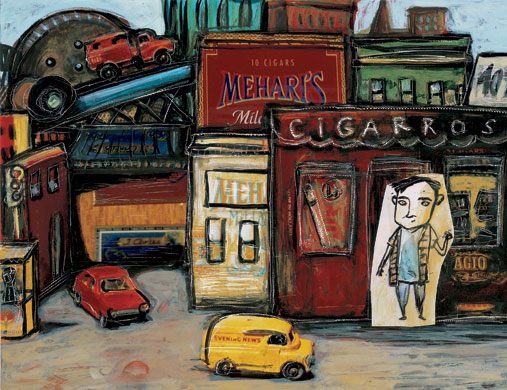

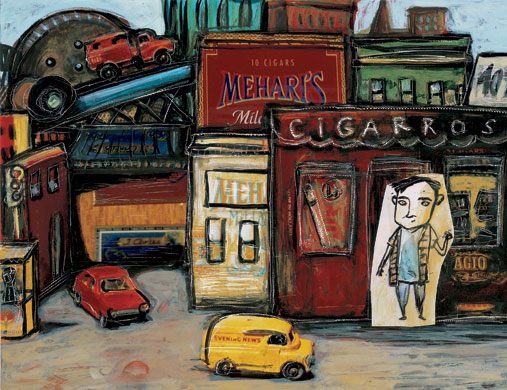

The Guardian has published a gallery of twelve beautiful pictures, which accompany a new edition of Paul Auster’s famed “Auggie Wren’s Christmas Story.” The story first appeared in the New York Times in 1990, and has been reprinted many times since. You can listen to Paul Auster read it on NPR. And of course the character of Auggie Wren appears in another Auster production, the film Smoke, which starred Harvey Keitel.

Illustration: ISOL/Faber and Faber

A few weeks ago, a friend of mine wrote to tell me how impressed he had been by a lecture on the challenges of social democracy that Tony Judt gave at New York University. Fortunately, the text of this talk is now available at the New York Review of Books. Here is a small excerpt

But my concern tonight is the following: Why is it that here in the United States we have such difficulty even imagining a different sort of society from the one whose dysfunctions and inequalities trouble us so? We appear to have lost the capacity to question the present, much less offer alternatives to it. Why is it so beyond us to conceive of a different set of arrangements to our common advantage?

Our shortcoming—forgive the academic jargon—is discursive. We simply do not know how to talk about these things. To understand why this should be the case, some history is in order: as Keynes once observed, “A study of the history of opinion is a necessary preliminary to the emancipation of the mind.” For the purposes of mental emancipation this evening, I propose that we take a minute to study the history of a prejudice: the universal contemporary resort to “economism,” the invocation of economics in all discussions of public affairs.

For the last thirty years, in much of the English-speaking world (though less so in continental Europe and elsewhere), when asking ourselves whether we support a proposal or initiative, we have not asked, is it good or bad? Instead we inquire: Is it efficient? Is it productive? Would it benefit gross domestic product? Will it contribute to growth? This propensity to avoid moral considerations, to restrict ourselves to issues of profit and loss—economic questions in the narrowest sense—is not an instinctive human condition. It is an acquired taste.

You can read the lecture in full here.

A few weeks ago, when I heard that Farrar, Straus and Giroux was publishing a new volume of Mahmoud Darwish’s poetry, I was thrilled. But I was also a little disappointed that such recognition would come after his passing. (Darwish has been published in the United States before, of course, though never by a major commercial press.) The book is called If I Were Another, and it is translated by Fady Joudah.

“If I Were Another” (Farrar, Straus and Giroux) presents long poems from the latter part of Mr. Darwish’s career—the only part that the poet, persistently self-critical, regarded as “mature.” These “lyric epics,” drawn from four collections, weave together many settings and voices. An elegy for the author’s father is followed by a polyvocal poem spoken by birds; a series on Andalusia, by the monologue of a Native American.

You can read more on the book at Speakeasy, the WSJ‘s book blog. Joudah previously translated the lovely volume The Butterfly’s Burden, published by Copper Canyon Press.

From the title story in Tim O’Brien’s The Things They Carried:

First Lieutenant Jimmy Cross carried letters from a girl named Martha, a junior at Mount Sebastian College in New Jersey. They were not love letters, but Lieutenant Cross was hoping, so he kept them folded in plastic at the bottom of his rucksack. In the late afternoon, after a day’s march, he would dig his foxhole, wash his hands under a canteen, unwrap the letters, hold them with the tips of his fingers, and spend the last hour of fight pretending. He would imagine romantic camping trips into the White Mountains in New Hampshire. He would sometimes taste the envelope flaps, knowing her tongue had been there. More than anything, he wanted Martha to love him as he loved her, but the letters were mostly chatty, elusive on the matter of love. She was a virgin, he was almost sure. She was an English major at Mount Sebastian, and she wrote beautifully about her professors and roommates and midterm exams, about her respect for Chaucer and her great affection for Virginia Woolf. She often quoted lines of poetry; she never mentioned the war, except to say, Jimmy, take care of yourself. The letters weighed ten ounces. They were signed “Love, Martha,” but Lieutenant Cross understood that Love was only a way of signing and did not mean what he sometimes pretended it meant. At dusk, he would carefully return the letters to his rucksack. Slowly, a bit distracted, he would get up and move among his men, checking the perimeter, then at full dark he would return to his hole and watch the night and wonder if Martha was a virgin.