Category: literary life

I want your vote! And the best part is this: I won’t make you, the voter, any promises I can’t keep. Actually, I won’t make you any promises at all. The editors of World Literature Today have chosen my essay “So to Speak” as one of their five favorites of the past decade. Here is how it begins:

Not long ago, while cleaning out my bedroom closet, I came across a box of old family photographs. I had tied the black-and-white snapshots, dog-eared color photos, and scratched Polaroids in small bundles before moving from Morocco to the United States. There I was at age five, standing with my friend Nabil outside Sainte Marguerite-Marie primary school in Rabat; at age nine, holding on to my father’s hand and squinting at the sun while on vacation in the hill station of Imouzzer; at age eleven, leaning with my mother against the limestone lion sculpture in Ifrane, in the Middle Atlas. But the picture I pulled out from the bundles and displayed in a frame on my desk was the one in which I was six years old and sat in our living room with my head buried in Tintin and the Temple of the Sun.

You can read the essay in full here and, if you like it, you can vote for it here.

(Photo credit: Getty Images)

My review of Katherine Boo’s amazing book, Behind the Beautiful Forevers: Life, Death, and Hope in a Mumbai Undercity, appears in the latest issue of The Nation. Here is an excerpt:

During the year I spent in Casablanca, I noticed that slums were discussed in the press almost exclusively with the vocabulary of pathology. The karian were “dangerous.” They were places that “tainted” the city and had to be “eradicated.” One journalist called them “a gangrene”; another urged a “hunt for the slums.” The language became even more antagonistic after a failed terrorist attack in March 2007, when it was revealed that one of the suicide bombers, like those who had attacked the city four years earlier, had come from the slum of Sidi Moumen. I remember vividly a television reporter shoving a microphone in a woman’s face in Sidi Moumen and demanding to know why “your” youths did what they did.

I tell you all this because I want to explain why Katherine Boo’s first book, Behind the Beautiful Forevers, struck me with the force of a revelation. Unlike other reporters, who come to the slums in brief and harried visits, only when they have news to report or statistics to illustrate, Boo, a staff writer at The New Yorker, has chosen to chronicle the lives of slum-dwellers in the Indian city of Mumbai by spending more than three years with them, patiently listening to them talk about their aspirations, their struggles and their dilemmas.

Here is one dilemma, all the more disturbing for its banality. Fatima Sheikh, a crippled woman, lies on a bed in Burn Ward Number 10 at Cooper Hospital in Mumbai, an IV bag and a used syringe sticking to her skin. Abdul Hakim Husain, the teenager who is accused of pouring kerosene over Fatima’s body and setting it alight, is in the custody of officers from the Sahar Police Station. After assessing the situation, Asha Waghekar, a part-time schoolteacher and full-time fixer, makes what she deems a very fair offer: Abdul Hakim’s parents can pay her 1,000 rupees and she will persuade Fatima to drop the charges.

You can read the full review here, and you can subscribe to The Nation here.

Recently, NPR’s Talk of the Nation did a series of segments on “common reads.” (These are programs in which incoming college freshmen in the U.S. are required to read the same book over the summer holiday and then discuss it in their first few classes.) Popular selections this year include The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, The Other Wes Moore, and Guns, Germs, and Steel, among others.

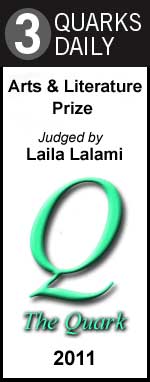

Now, I didn’t do my undergraduate studies in the United States, so I had no idea what “common readings” were until Hope and Other Dangerous Pursuits was selected for the Life of the Mind program at the University of Tennessee, back in 2006. Over the course of three days, I visited the campus, spoke to several classes, and gave a public lecture. Since then, I’ve done quite a few common readings, the most recent of which was earlier this week at Wingate University in North Carolina, where first-year students (a term I much prefer to “freshmen”) read Hope. I always find it fun to talk to younger students about the book; they always have the most interesting (and often unusual!) questions.

Photo credit: Ibarionex Perello. This was taken at a reading at the now defunct Dutton’s Books.

One of the books I’ve discussed with my creative nonfiction students this quarter is Zeitoun, Dave Eggers’ compelling account of Abdulrahman Zeitoun’s attempts to help fellow New Orleans residents stranded by Hurricane Katrina, Zeitoun’s eventual incarceration on charges that were never revealed to him, and his wife’s attempts to have him released. Because the book focuses on one individual’s subjective experience, it offers a version of the cataclysmic events in New Orleans that is radically different from the one we’ve seen on our television screens or read about in newspapers. (Remember, for instance, the babies-being-raped-in-the-Superdome story? Or the looting-gangs-roaming-the-streets-of-the-city story? Both false.)

Not long after we had wrapped up our discussion of Zeitoun, it was announced that Osama bin Laden had been killed in Pakistan. The news was covered uninterruptedly on our televisions and radios, in print and online. And yet I couldn’t help but wonder which details of the official story would change. A few, as it turned out. Bin Laden used his wife as a human shield, then he didn’t. He had a gun, then he didn’t. He resisted capture, then he didn’t. He was buried according to Islamic tradition, then he wasn’t. We may never really know what happened in Abbottabad a month ago, or maybe we will, many years from now, when the details of the story will no longer hold so much value—political, personal, mythological—for those who are telling it.

Photo credit: The Zeitoun Foundation.

A few weeks ago, the editors of 3 Quarks Daily, the magazine of eclectic online writing, asked me to judge their Arts & Literature Prize. (The prize is in its second year and was judged last year by Robert Pinsky. Prizes have also been offered in the areas of Science, Philosophy, and Politics.)

Nominations for the 2011 Arts & Literature Prize were opened in mid-February, submitted to a vote, and winnowed down to nine finalists earlier this month.

I enjoyed reading the nine entries very much and appreciated especially the wide variety of subjects and genres: book reviews, personal essays, critical essays, an open letter, and a poem. There was a lot of very strong writing but, in the end, I had to choose just three for the prize. You can find out who they are here.

Perhaps the most consistent irony about our mass media is that it’s curated, edited, customized, or otherwise filtered to such a degree that it is not mass at all. We hear only the news that is meant for us, and we scarcely stop to think about the news we’re not hearing. The recent mid-term elections seemed to me to be basically about different news being created for the benefit of different communities. It’s tempting to think of this as a thoroughly modern phenomenon, a by-product of the speed with which news circulates these days. But my recent foray into old travelogues and historical fiction has really shown me that the way we receive and interpret the news hasn’t changed very much. Take Beloved, for instance. (I’ll be using this book in one of my classes next quarter, which is why it came to mind.) Late in the novel, Toni Morrison writes about how two different racial communities in nineteenth-century Cincinnati perceive and interpret a very specific piece of news. The scene takes place about two-thirds of the way into the novel, when Paul D., a former slave, finds out a secret about Sethe, the woman he loves. Stamp Paid is the man who brings the press clipping (with this secret) to Paul:

Paul D. slid the clipping out from under Stamp’s palm. The print meant nothing to him so he didn’t even glance at it. He simply looked at the face, shaking his head no. No. At the mouth, you see. An no at whatever it was those black scratches said, and not to whatever it was Stamp Paid wanted him to know. Because there was no way in hell a black face could appear in a newspaper if the story was about something anybody wanted to hear. A whip of fear broke through the heart chambers as soon as you saw a Negro’s face in a paper, since the face was not there because the person had a healthy baby, or outran a street mob. Nor was it there because the person had been killed, or maimed or caught or burned or jailed or whipped or evicted or stomped or raped or cheated, since that could hardly qualify as news in a newspaper. It would have to be something out of the ordinary—something whitepeople would find interesting, truly different, worth a few minutes of teeth sucking if not gasps. And it must have been hard to find news about Negroes worth the breath catch of a white citizen in Cincinnati.

There is some back-and-forth as Stamp tries to convince Paul D. to look at the article about Sethe in the paper, even as he’s trying to justify for himself why no one warned Sethe that a slave catcher was headed toward her house.

Stamp Paid looked at him. He was going to tell him about how restless Baby Suggs was that morning, how she had a listening way about her; how she kept looking down past the corn to the stream so much he looked too. In between ax swings, he watched where Baby was watching. Which is why they both missed it: they were looking the wrong way—toward water—and all the while it was coming down the road. Four. Riding close together, bunched-up like and righteous. He was going to tell him that, because he thought it was important: why he and Baby Suggs both missed it. And about the party too, because that explained why nobody ran on ahead; why nobody sent a fleet-footed son to cut ‘cross a field soon as they saw the four hourses in town hitched for watering while the riders asked questions. Not Ella, not John, not anybody ran down or to Bluestone Road, to say some new whitefolks with the Look just rode in. The righteous Look every Negro learned to recognize along with his ma’am’s tit. Like a flag hoisted, this righteousness, telegraphed and announced the faggot, the whip, the fist, the lie, long before it went public.

Some pay attention only to what’s in the newspaper, to declarations from police officials and accompanying pictures; others have to keep their ears trained on the noises coming from the road, and then ‘telegraph’ them elsewhere. The juxtaposition is so skillfully weaved into the scene that I didn’t notice it the first time I read it. (Nor did I realize that the character of Sethe was based on a real-life runaway slave, who attracted the attention of Ohio newspapers because of what she had done. One of the reasons I really enjoyed re-reading the book was because of all the things I’m noticing now that I didn’t notice years ago.)

Photo credit: Alfred Eisenstaedt/Time & Life Pictures/Getty Images