Category: literary life

Earlier this week, the Irish novelist Colm Toíbín told an interviewer for the Guardian (MJ Hyland, herself a novelist) that he found no enjoyment in writing:

“Oh there’s no pleasure. Except that I don’t have to work for anyone who bullies me,” he said in response to Hyland’s question about how writing makes him feel. “I write with a sort of grim determination to deal with things that are hidden and difficult and this means, I think, that pleasure is out of the question. I would associate this with narcissism anyway and I would disapprove of it.”

The only aspect of writing he liked, he said, was getting paid. Now other writers, including AL Kennedy, Hari Kunzru, and Joyce Carol Oates, are chiming in with their stories of what they like or dislike about their profession. I think AL Kennedy sums up my feelings when she says, “The joy of writing for a living is that you get to do it all the time. The misery is that you have to, whether you’re in the mood or not.”

Apropos of Margaret Atwood. Earlier this month, the British novelist Geraldine Bedell, author of The Gulf Between Us, claimed to have been dis-invited from the Emirates Airlines Festival of Literature, where her book was supposed to be launched, because it contained a gay sheik character. She also claimed that The Gulf Between Us had been banned from sale in the, well, Gulf. Bedell protested; several authors rose to her defense and in support of freedom of speech; the venerable Margaret Atwood canceled her appearance at the festival; there was a major hoopla in London newspapers. Here’s The Times, for instance: “Geraldine Bedell’s novel banned in Dubai because of gay character.” And here’s The Telegraph: “British author Geraldine Bedell banned from Dubai book festival.”

Only now, after all this exposure and publicity, does the image get a little more complicated. If you read the articles linked to above, you’ll notice that the source appears to be Bedell herself and an email from the festival’s director, Isobel Abulhoul. You’ll also notice that the book is not due out until April, which makes it a little hard to claim that it was “banned” from sale. After the initial controversy, Abulhoul came forward to say that she was in fact approached by Bedell’s publisher for a possible launch of the novel at the festival. She read the manuscript, decided it wasn’t right for the festival, and said no. One can safely assume she wasn’t expecting her email to be leaked to the press. Margaret Atwood wrote a funny, self-deprecating piece for the Guardian, explaining how she was fooled into thinking this was a clear-cut case of censorship:

From reading the press, I got the impression that her book had been scheduled to launch at the festival, and that the launch had then been cancelled, for whiff-o’gay-sheikh reasons; and that, furthermore, it had been banned throughout the Gulf states; and that furthermore, Bedell herself had been prohibited from attending the festival, and also from travelling in Dubai. So said TheCelebrityCafe.com and other commentators.

This was a case for Anti-Censorship Woman! I nipped into the nearest phone booth, hopped into my cape and coiled my magic lasso, and swiftly cancelled my own appearance; because, as a vice-president of International PEN, I could not give my August Seal of Elderly Writer Approval to such a venue.

Well done, Anti-Censorship Woman! was the response. How stalwart!

But possibly not.

You can read Atwood’s response in full here.

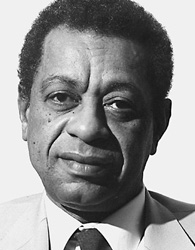

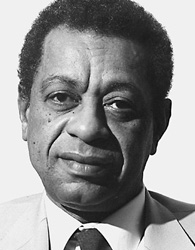

I was terribly saddened to hear that the great Sudanese novelist, short story writer and literary critic Tayeb Salih passed away in London yesterday. He was eighty years old. A few months ago, when I was preparing my introduction to the new edition of Season of Migration to the North, I had considered going to London to interview him. But then life intervened: I was busy and thought I might be able to meet him some other time. That time never came. He published only a handful of novels, but each had the beauty and complexity of dozens of literary works.

I was terribly saddened to hear that the great Sudanese novelist, short story writer and literary critic Tayeb Salih passed away in London yesterday. He was eighty years old. A few months ago, when I was preparing my introduction to the new edition of Season of Migration to the North, I had considered going to London to interview him. But then life intervened: I was busy and thought I might be able to meet him some other time. That time never came. He published only a handful of novels, but each had the beauty and complexity of dozens of literary works.

The BBC announced the news on Tuesday morning and included a short audio remembrance by Khaled Mubarak, a friend and colleague and Salih’s. There is quite a bit of coverage in the Arabic press, of course. (See, for instance, Al-Hayat, Ad-Dustour, or Elaph.) In Ash-Sharq Al-Awsat, Talha Jibril reveals that Salih’s body will be interred in Omdurman, in the Sudan, on Friday of this week.

Salih’s work is available in English thanks to translations by Denys Johnson-Davies: Season of Migration to the North, The Wedding of Zein, and Bandarshah. If you have never read him, I envy you your first experience.

In the Nation, Alexander Provan wonders whether Kafka’s work has nowadays been reduced to what he calls “a one-word slogan”: Kafkaesque.

What is the Kafkaesque? It is the scene described in Kafka’s story “A Report to an Academy,” in which an eloquent ape candidly recounts his arduous path toward civilization: “There is an excellent idiom: to fight one’s way through the thick of things; that is what I have done.” It is, Begley suggests, that familiar existential predicament so often played out by Kafka’s characters, who “struggle in a maze that sometimes seems to have been designed on purpose to thwart and defeat them. More often, the opposite appears to be true: there is no purpose; the maze simply exists.” It is the explosion of the international market for mortgage-backed securities and derivatives, in which value is not attached to the thing itself but to speculation on an invented product tangentially related to (but not really tied to) that thing. It is FEMA’s process for granting housing assistance after Hurricane Katrina: victims were routinely informed of their applications’ rejection by letters offering not actual explanations but “reason codes.” It is the Bush administration’s declaration that certain Guantánamo Bay detainees who had wasted away for years without trial were “no longer enemy combatants” and its simultaneous refusal to release them or clarify whether they had ever been such. It is, as Walter Benjamin wrote, “the form which things assume in oblivion.” “Kafkaesque,” in other words, is a phrase that has come to represent very much about modern life while signifying very little.

Provan reviews several recent books on Kafka, including one by Milan Kundera, who, interestingly enough, seems to blame Max Brod for starting the deification trend that resulted in vague terms like “Kafkaesque.”

At the L.A. Times book blog, Jacket Copy, Carolyn Kellogg reports that a long-neglected short story by John Cheever is being republished online this week, at Five Chapters. “Of Love: A Testimony” was originally released in 1943, but has not been anthologized or reprinted since. Here is its opening line:

He was as good a representative of his class as you could find, born in a staid suburb, educated in mediocre schools, firmly grounded in the cynicism of his class and education.

In its aim to immediately situate the protagonist within a specific class and education level, it reminds me a bit of the opening line to another Cheever story, “The Enormous Radio”:

Jim and Irene Wescott were the kind of people who seem to strike that satisfactory average of income, endeavor, and respectability that is reached by the statistical reports in college alumni bulletins.

At any rate, any Cheever story is a treat, so I look forward to reading this one. It will appear in five installments. Here is the first.

Twenty years ago today, Salman Rushdie received what he would later describe as a “funny valentine.” The Ayatollah Khomeini issued a fatwa on Radio Tehran, calling Rushdie an apostate and sentencing him to death for his work of fiction, The Satanic Verses. The fatwa followed weeks of protests by some people within the British Muslim community and led to further protests and riots in parts of the Muslim world. One translator, several dozen protesters, and many supporters were murdered as a result of the controversy. Hundreds of others—editors, publishers, booksellers, readers, bystanders—were injured. Rushdie had to live under police protection for nine years.

Nowadays, Rushdie often quips that, without seeking further argument with the Ayatollah, “I will point out that only one of us is dead.” I’m glad it was the novelist who survived the confrontation, not the politician/religious nutjob. I remember getting my hands on a copy of the book when I was in London in 1990; I couldn’t understand what the fuss was all about. But then again, I wasn’t someone whose identity was threatened by novels. The Satanic Verses is not my favorite of Rushdie’s books (those would be Midnight’s Children and Imaginary Homelands). I don’t always agree with what he writes, but whenever I think about what he and his family went through for several years, I feel enormous sympathy for him.

The BBC has a short interview with three people who took part in the original protests in Bradford. Meanwhile, the Guardian catches up with Iqbal Sacranie (he who said that “death would be too easy” for Rushdie) and Lisa Appignanesi (the novelist and memoirist who tirelessly defended Rushdie.) As for the author, he’s been busy; the paperback edition of his tenth novel, The Enchantress of Florence, was released last month.

I was terribly saddened to hear that the great Sudanese novelist, short story writer and literary critic

I was terribly saddened to hear that the great Sudanese novelist, short story writer and literary critic