I’m thrilled to report that The Moor’s Account has won the Hurston/Wright Legacy Award in fiction. I was not expecting the novel to take the prize—there were so many great books in consideration—but it was a special treat to see it being recognized at the Washington, DC gala. The other two finalists were Tiphanie Yanique (picture above, left) and Roxane Gay.

In other news, I had a new essay on the theme of ‘unforgettable meals’ in The New York Times Magazine this week. Here’s how it starts:

Moha, who wanted to be our guide, said it was an easy hike to the Bridge of God. But he looked about 15 and spoke in a timid voice that made me doubt how easy it would really be. We were at the trailhead in Akchour, a small village nestled in the Rif Mountains in northern Morocco. ‘‘How long will it take?’’ my daughter asked.

I translated her question into Arabic for Moha. ‘‘It depends how fast we walk,’’ he replied. ‘‘With small children, three or four hours.’’ The adults in our party were eager to do the hike; the children, not so much. Something is always lost in translation, but as Salman Rushdie once put it, something can also be gained. ‘‘Only a couple of hours,’’ I said in English.

You can read the rest here.

I’ll be closing my fall tour with an event in Santa Fe, New Mexico, where I’ll be in conversation with the novelist Aminatta Forna for the Lannan Foundation. Tickets for the event are available here.

(Photo credit: Don Baker / Hurston Wright Foundation.)

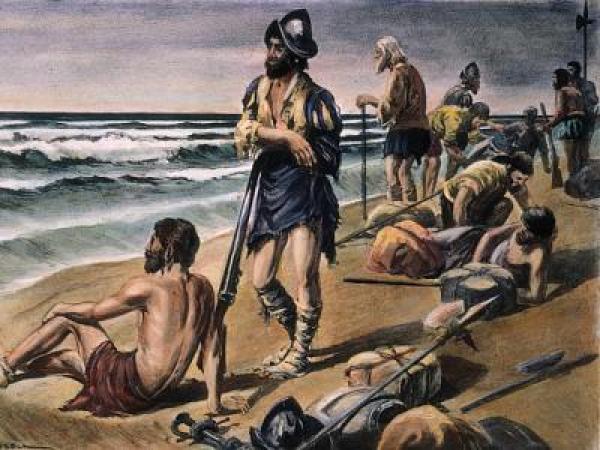

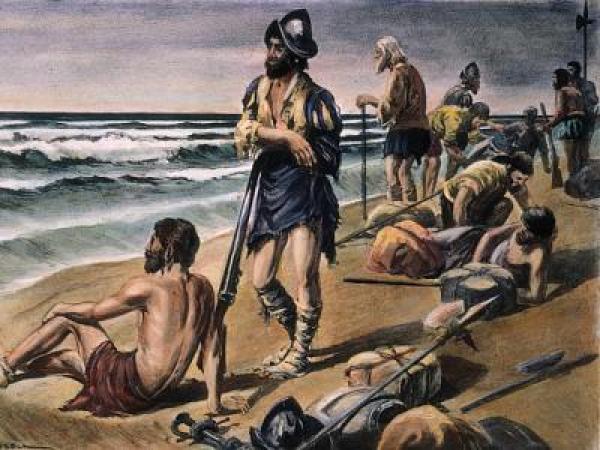

While writing The Moor’s Account, I became curious about visual representations of Estebanico (a.k.a. Mustafa al-Zamori). As it turned out, the incredible story of the Narváez expedition inspired quite a few painters. Below, for instance, is the depiction of the Narváez castaways that Penguin Classics used for its cover of Cabeza de Vaca’s Chronicle. You will notice that Estebanico appears nowhere in it.

But as time passed and scholarship evolved, interest in Estebanico also grew. Here is a painting by José Cisneros, where Estebanico appears alongside the other three survivors, Andrés Dorantes, Alonso del Castillo, and Cabeza de Vaca. (Estebanico is second from right.)

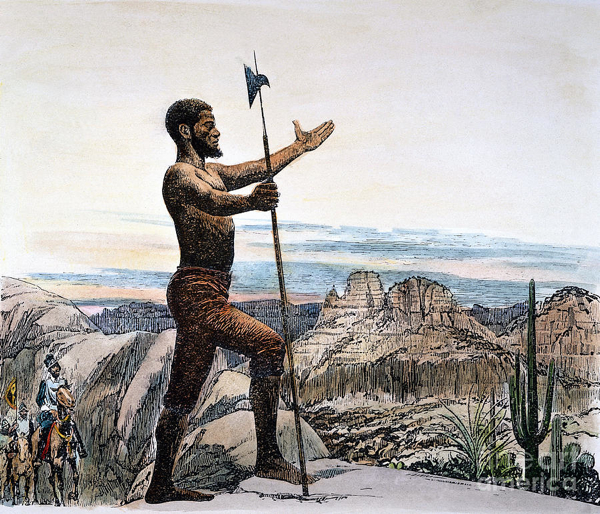

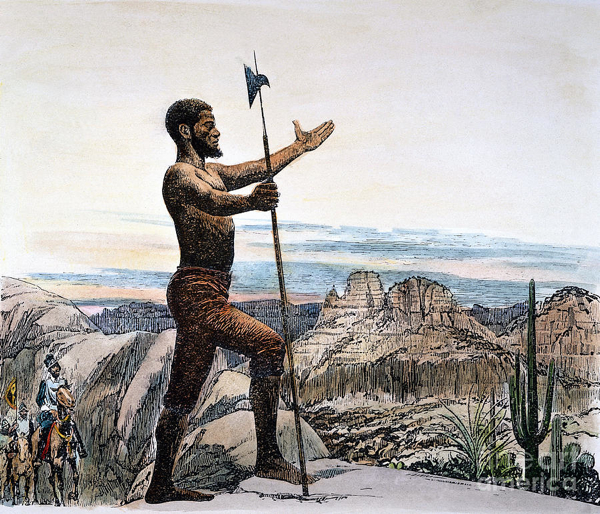

It’s interesting to note the differences between artist depictions when it comes to style and dress. In the one below, for example, Estebanico appears shirtless and carrying a halberd, leading the way for the Coronado expedition, which took place many years after the Narváez expedition.

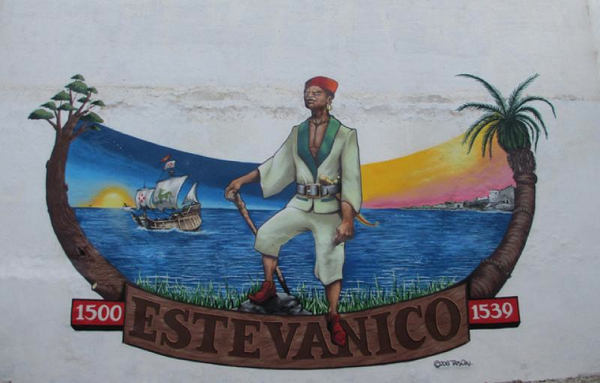

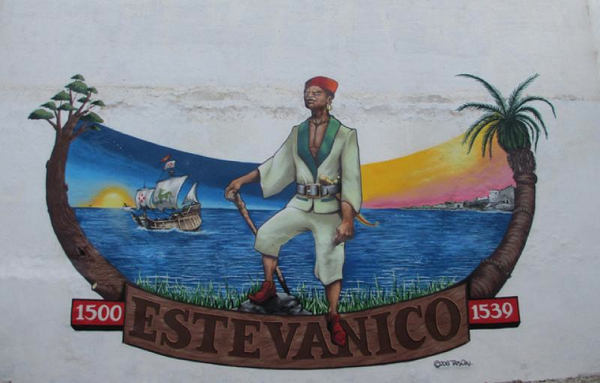

In his hometown of Azemmur, there are a few murals dedicated to the explorer. Here is one where Estebanico is portrayed in the dress and style of a pirate. (Of course, he was no pirate; he was a slave turned scout turned faith healer.)

Adjacent to that mural in Azemmur is another one, also depicting Estebanico. Here, the explorer is shown wearing a turban and a loincloth, and carrying a wooden lance.

What I find fascinating about all these images is what they tell us not about Estebanico, but about the artists themselves. Each one had a different view of the explorer, shaped by his or her culture and experience of history.

Image credits:

1. Alfred Russell, Alvar Nuñez Cabeza de Vaca and His Companions Lost on the Shore of the Gulf of Mexico, 1528. The Granger Collection. New York.

2. José Cisneros, Cabeza de Vaca and His Three companions on the Texas Coast. Museum of South Texas History.

3. Artist unknown, Estevanico. The Granger Collection. New York.

4. Artist name illegible, Estevanico/Estebanico El Azemmouri. MonMaroc Guide.

5. Koukou. Estebanico. Azemmur.

Five years ago this week, Moroccan literature lost one of its greats, the novelist Driss Chraïbi. I wanted to post a short excerpt from Le Passé Simple, his first novel and perhaps the most widely studied of his works. It tells the story of a young man who violently rebels against the edicts of his father, a tea merchant from Mazagan. When it was published in 1954, Le Passé Simple created a huge controversy in Morocco. The country was still in the midst of its struggle for independence. Many Moroccan intellectuals didn’t look kindly on a book that virulently criticizes traditional Moroccan modes of living and ends with the main character leaving for France, and, as a final act of goodbye, uses the bathroom on the airplane, in the hope that “every drop falls on the heads of those I know well, who know me well, and whom I despise.” In France, the reaction was quite the opposite; the book was quite well reviewed, perhaps serving as “proof” that Morocco needed France’s civilizing influence.

But Le Passé Simple is much more than a simple cry of revolt. Yes, it is full of anger at the father character (referred to throughout as “Le Seigneur,” that is, “The Lord”); at the treatment of women; at the teaching in Quranic schools; at the hypocrisy of Moroccan society; and so on. But there are also moments of tenderness for both the father and the mother, for books, for the joys of teenage life. There is a strong emphasis on the powerlessness of silence and fear–the mother is silent, the children are silent–and so, necessarily, on the power of the word. It’s a beautifully written novel, with moments of great lyricism.

Un après midi, j’ai fait l’école buissonnière sans m’en rendre compte. J’ai erré dans les rues , siffloté avec les oiseaux, suivi le vol des nuages. Finalement, je me suis perdu. Une vieille femme m’a rencontré, m’a embrassé, m’a donné deux sous. J’ai mis la pièce dans une boîte d’allumettes vide ramassée quelque part.

Vers le soir, je vis une silhouette connue qui venait à ma rencontre à grandes enjambées. Ce n’était autre que mon digne et respecté père. Le règlement de compte, entre lui et moi, se fit, à mes dépens, en trois actes.

ACTE Ier: Nous passâmes rassurer le maître d’école. Afin de profiter d’une si bonne occasion de se démontrer le dévouement qu’il s’acharnaient à avoir l’un pour l’autre (selon les traités verbaux jurés bilatéralement le jour de mon inscription) mon père me bascula en l’air et le maître cingla la plante de mes pieds une bonne centaine de fois. Nous prîmes Camel au passage et allâmes tous trois a la maison.

ACTE II: Rentrés chez nous, après maintes explications, les salamalecs et pleurs de soulagement de ma mère, la même scène que tout à l’heure recommença, mais avec un léger correctif. Ce fut maman, trop heureuse de voir, qui maintint mes jambes et mon père qui fit tournoyer le bâton. Une demi-heure durant.

ACTE III: Les pieds en sang, je me jette dans les bras de ma mère, largement ouverts et consolateurs. Mon père n’admet pas de faiblesse, nous corrige tous en conséquence, et sort en claquant les portes. Nous restons, là, Camel, ma mère et moi, à nous lamenter comme des pleureuses juives.

EPILOGUE: Plus tard, je me souviens, je souris, je pêche dans ma poche la boîte d’allumettes, l’ouvre et montre ce qu’elle contient. J’ai quand même gagné deux sous dans ma journée.Maman les serre précieusement dans sa ceinture et m’embrasse.

I don’t own an English translation of the book (and I believe the one that was published some years ago by Counterpoint is out of print.) But here is my translation of the passage, for your enjoyment:

One afternoon, I skipped school, without realizing it. I wandered in the streets, whistled away with the birds, followed the flight of the clouds. Eventually, I got lost. An old woman saw me, kissed me, gave me two cents. I put the coin in a matchbox I picked up somewhere.

Toward evening, I saw a familiar figure coming toward me in large strides. It was none other than my dignified and respected father. The settling of accounts, between us, was done at my expense in three acts:

ACT I: We stopped by to reassure the schoolteacher. My father and the teacher used this opportunity to demonstrate the devotion they continued to have for one another (according to the verbal treaties sworn bilaterally on the day of my registration). My father tipped me up and the teacher whipped the soles of my feet a good hundred times. Then we picked up Kamal and went all three of us to the house.

ACT II: Once at home, after many salams, explanations, and cries of relief from my mother, the same scene unfolded anew, but with a slight change. It was my mother, too happy to see me, who held my legs and my father who used the stick. For half an hour.

ACT III: My feet bloody, I throw my self in my mother’s arms, open and consoling. My father does not admit a weakness, and therefore corrects all of us by leaving, slamming the doors behind him. We remain there, Kamal, my mother and me, moaning like Jewish funeral criers.

EPILOGUE: Later, I remember, I smile, I fish out of my pocket the matchbox, open it and show what it contains. I have, after all, earned two cents that day. Maman carefully ties them inside her belt and kisses me.

Chraibi lived in France and didn’t return to Morocco for many, many years. But he wrote other novels; Morocco got its independence; life went on. When he returned in early 1985, attitudes, too, had changed. University and high school students, many of whom were engaged in organizations that opposed the regime, had a completely different attitude to his work. (The influential magazine Souffles defended his work in a long article, too. ) In the end, he became the prodigal son.

Photo credit: MarocCulture

The latest issue of Newsweek magazine includes an essay I wrote about returning to Morocco in February, one year after the protests began. Here is how the piece opens:

One afternoon in February, a few hours after I arrived in Casablanca from Los Angeles, I learned that my uncle A., a generous man with a troubled soul, had died. I was putting my shoes on with one hand and checking my phone with the other, already running late for a panel discussion at the Casablanca Book Fair, when I saw the message. I was stunned, not just by the news of his death—he was only 73, after all, and although he suffered from diabetes, he was otherwise healthy—but by the realization that I had missed his funeral.

In the Muslim tradition, a body is interred as soon as possible after death. The hospital notified our family of A.’s passing a little after midnight; by morning, he was already washed, shrouded, and prepared for funeral prayers; by lunchtime he was buried at Martyrs’ Cemetery in Rabat, Morocco’s capital city. Because I had silenced my phone, and because I had slept through my jet lag, I had found out about his death only after he had been laid to rest.

To be an immigrant is to live a divided life—a part of you lives in one country, the other part in another. You speak two languages, read two sets of newspapers, hear the conversations of two nations. You learn to dread the moments when the two worlds come together abruptly—like when your phone rings in the middle of the night. Twice already I have had to find out in this way about the death of a loved one. This time, I was in Morocco, but I had somehow managed to be as absent as if I had remained in America.

You can read the essay in full on the website of Newsweek.