News

Here is a brief excerpt from Ian McEwan’s Atonement, from the scene in which thirteen-year-old Briony laments having written a play for her brother Leon, instead of a short story:

The title lettering, the illustrated cover, the pages bound—in that word alone she felt the attraction of the neat, limited and controllable form she had left behind when she decided to write a play. A story was direct and simple, allowing nothing to come between herself and her reader—no intermediaries with their private ambitions or incompetence, no pressures of time, no limits on resources. In a story you only had to wish, you only had to write it down and you could have the world; in a play you had to make do with what was available: no horses, no village streets, no seaside. No curtain. It seemed so obvious now that it was too late: a story was a form of telepathy. By means of inking symbols onto a page, she was able to send thoughts and feelings from her mind to her reader’s. It was a magical process, so commonplace that no one stopped to wonder at it. Reading a sentence and understanding it were the same thing; as with the crooking of a finger, nothing lay between them. There was no gap during which the symbols were unraveled. You said the word castle, and it was there, seen from some distance, with woods in high summer spread before it, the air bluish and soft with smoke rising from the blacksmith’s forge, and a cobbled road twisting away into the green shade…”

I just started work on a new short story, which, I suppose, is what reminded me of this passage from Atonement.

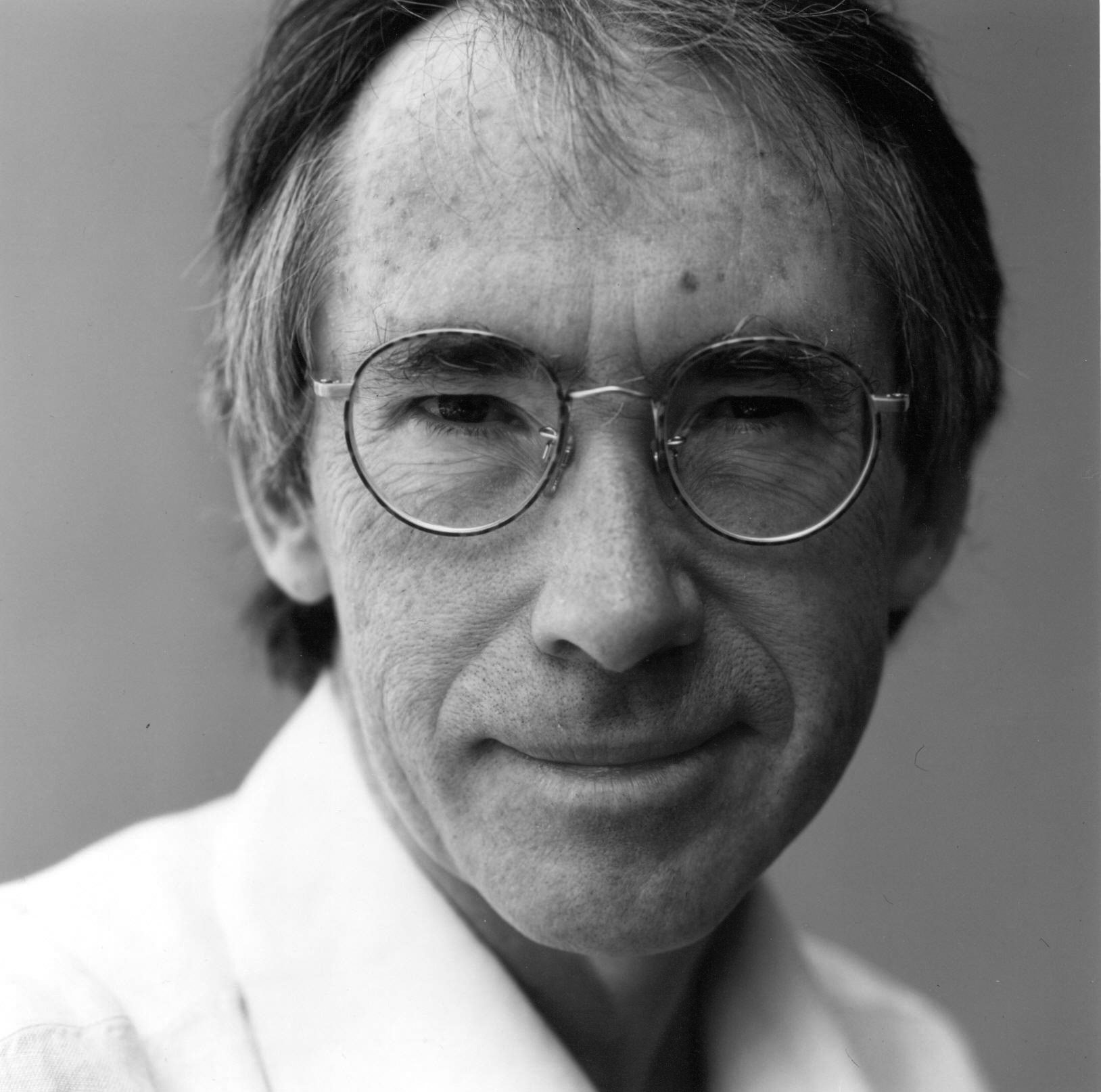

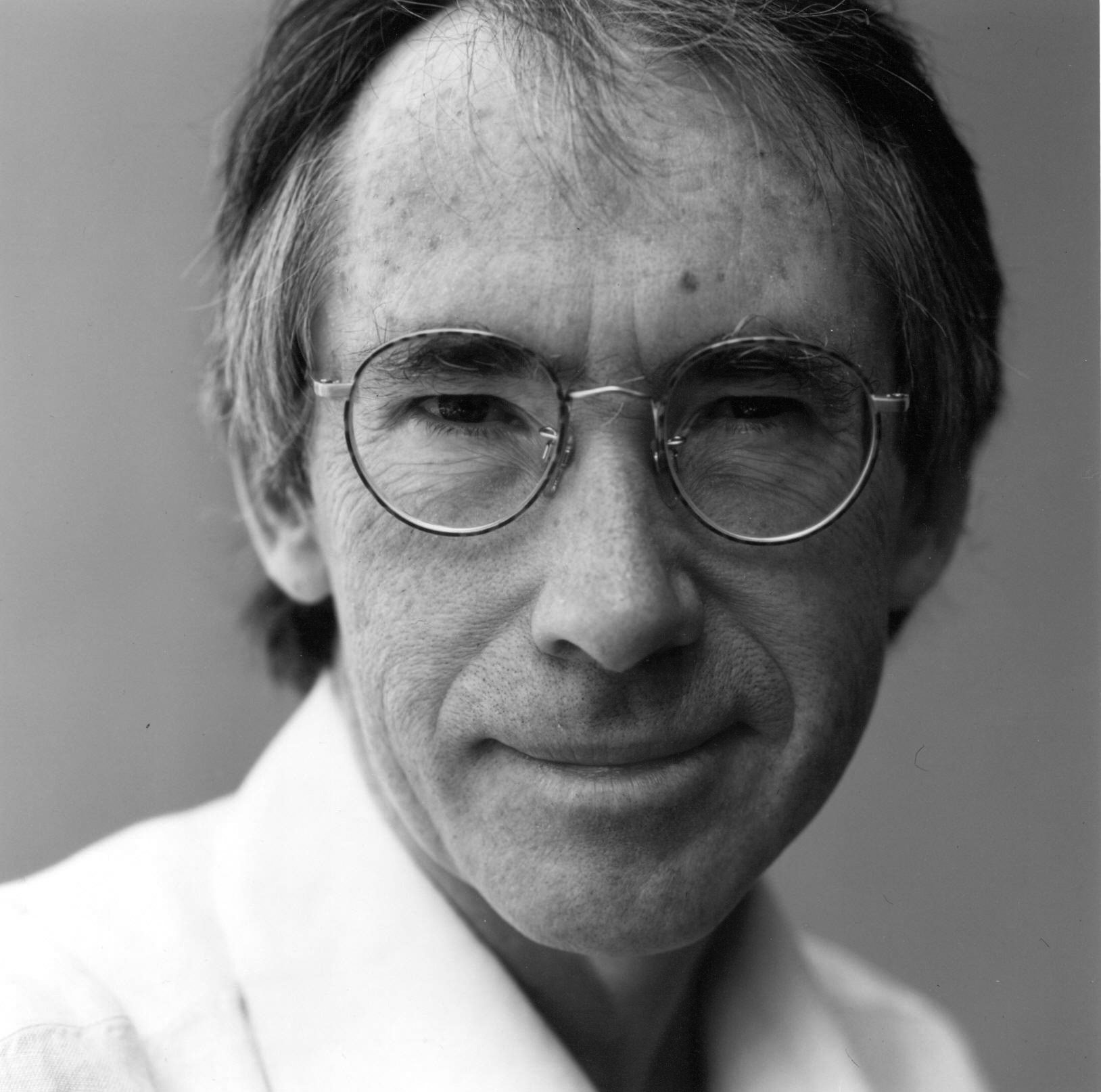

Photo: Eamon McCabe.

The most recent issue of the London Review of Books includes a thought-provoking cover story by the writer and academic Walter Benn Michaels. The essential argument of “What Matters” is that, while the United States has made some progress in the last forty years in matters of sexual and racial equality, it has remained virtually unchanged when it comes to class inequality.

No group dedicated to ending economic inequality would be thinking today about declaring victory and going home. In 1969, the top quintile of American wage-earners made 43 per cent of all the money earned in the US; the bottom quintile made 4.1 per cent. In 2007, the top quintile made 49.7 per cent; the bottom quintile 3.4. And while this inequality is both raced and gendered, it’s less so than you might think. (…)

An obvious question, then, is how we are to understand the fact that we’ve made so much progress in some areas while going backwards in others. And an almost equally obvious answer is that the areas in which we’ve made progress have been those which are in fundamental accord with the deepest values of neoliberalism, and the one where we haven’t isn’t. We can put the point more directly by observing that increasing tolerance of economic inequality and increasing intolerance of racism, sexism and homophobia – of discrimination as such – are fundamental characteristics of neoliberalism. Hence the extraordinary advances in the battle against discrimination, and hence also its limits as a contribution to any left-wing politics. The increased inequalities of neoliberalism were not caused by racism and sexism and won’t be cured by – they aren’t even addressed by – anti-racism or anti-sexism. (…)

American universities are exemplary here: they are less racist and sexist than they were 40 years ago and at the same time more elitist. The one serves as an alibi for the other: when you ask them for more equality, what they give you is more diversity.

I found the article to be refreshing; I’ve always thought that class is a huge taboo in the United States. It’s rarely ever discussed, and when it is, it’s usually in terms of its interaction with race. But I also think Michaels overstates his points considerably. Take, for instance, the case of the recent arrest of Henry Louis Gates, which Michaels describes thus:

The recent furore over the arrest for ‘disorderly conduct’ of Henry Louis Gates helps make this clear. Gates, as one of his Harvard colleagues said, is ‘a famous, wealthy and important black man’, a point Gates himself tried to make to the arresting officer – the way he put it was: ‘You don’t know who you’re messing with.’ But, despite the helpful hint, the cop failed to recognise an essential truth about neoliberal America: it’s no longer enough to kowtow to rich white people; now you have to kowtow to rich black people too. The problem, as a sympathetic writer in the Guardian put it, is that ‘Gates’s race snuffed out his class status,’ or as Gates said to the New York Times, ‘I can’t wear my Harvard gown everywhere.’ In the bad old days this situation almost never came up – cops could confidently treat all black people, indeed, all people of colour, the way they traditionally treated poor white people. But now that we’ve made some real progress towards integrating our elites, you need to step back and take the time to figure out ‘who you’re messing with’. You need to make sure that nobody’s class status is snuffed out by his race.

Michaels’ assertion that “in the bad old days…cops could confidently treat all black people, indeed, all people of color, the way they traditionally treated poor white people” is simply inaccurate. All other things being equal (which of course they never are, but bear with me for the sake of the argument), race does play a role in the way in which cops treat people. And you don’t need to take my word for it; just look at statistics emanating from police departments in cities like Los Angeles. If a poor white man drove a Rolls Royce in Beverly Hills, he would not necessarily be stopped, while a rich black man might, as famously happened to the lawyer Johnnie Cochran in 1979. The fact remains that racism does play a role that cannot be entirely explained away by an appeal to class. Still, I think the article is interesting, because it explains why the focus on race and sex at the expense of class legitimates disparities and perpetuates prevailing power structures.

I have an essay in the September issue of World Literature Today, on the topic of writing in one’s third language. Here is the opening paragraph:

Not long ago, while cleaning out my bedroom closet, I came across a box of old family photographs. I had tied the black-and-white snapshots, dog-eared color photos and scratched Polaroids in small bundles before moving from Morocco to the United States. There I was at age five, standing with my friend Nabil outside Sainte Marguerite-Marie primary school in Rabat; at age nine, holding on to my father’s hand and squinting at the sun while on vacation in the hill station of Imouzzer; at age eleven, leaning with my mother against the limestone lion sculpture in Ifrane, in the Middle Atlas. But the picture I pulled out from the bundles and displayed in a frame on my desk was the one in which I was six years old and sat in our living room with my head buried in Tintin and the Temple of the Sun.

The essay is available in its entirety online. I hope you enjoy reading it. You can subscribe to WLT here.

This summer I did what I had promised myself for many years I would do: take a proper holiday. I stayed away from the internet, the television, and the mobile phone. Instead, I spent time with family and friends; walked, swam and hiked; read four books and took notes; ate loads of grilled fish, meat tagines and pasta arrabiatta (appropriately enough); bought lots of books; stayed up, slept late, or woke early, depending on the day; bargained for souvenirs and knickknacks; and generally just tried to focus on the moment. It was great to be away. But now I am back and of course I have many, many emails to sift through, deadlines to meet, and various appointments to make. More tomorrow.

I am still (thankfully, blissfully, perhaps even embarrassingly) still on holiday. We went up to the town of Asilah for a week, which gave me a chance to catch a couple of the events at the annual summer festival there. Then we continued on to the beautiful town of Chaouen (or Chefchaouen) where we hiked up to Qantrat Sidi Rabbi (Bridge of God.) I’m now wrapping up my stay in Morocco and running around saying goodbye to everyone.