In Yosemite

We’re spending the Thanksgiving holiday at Yosemite National Park. I hope everyone has a safe and happy weekend. See you back here on Monday.

We’re spending the Thanksgiving holiday at Yosemite National Park. I hope everyone has a safe and happy weekend. See you back here on Monday.

I’ve always been amused by the prevailing idea in our culture that writers are anti-social creatures, people who would rather spend time alone in a room than have to speak to other sentient beings. The writers I’ve met come in all types, of course, but very few have really fit this cliché. In fact, I’ve noticed that whenever they are thrown together at a conference, a festival, or some other literary event, writers don’t mind gathering, late into the night, to talk. I rarely ever take part in these late-night chats, simply because I can’t handle them. I sleep, on average, between nine and ten hours a night. I can function on eight hours, if I have to. But if I’m forced, by circumstance, to get by with seven hours, I’m nearly useless.

When I was in Indiana last week, for instance, all the invited writers and artists wanted to go have drinks. It was almost midnight. I excused myself because I could barely think, let alone talk. They insisted. Why, they asked, could I not come just for a bit? I said I had to go to bed. Which, of course, sounded like the lamest, most ridiculous excuse to their ears. They looked at me sideways. I imagine they thought I was being standoffish. But, really, I was just exhausted, and already counting how many hours of sleep I could get. And the morning after? I was the last one to get up.

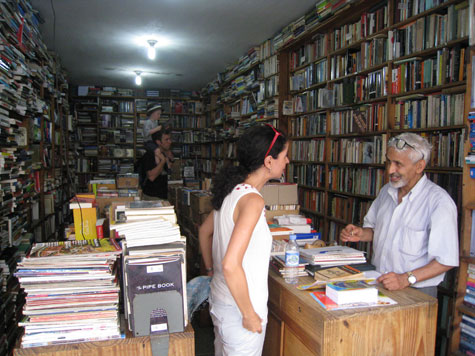

When I was an undergraduate at University Mohammed-V, I used to find all my English-language books at the aptly named English Bookshop in downtown Rabat. The store was so tiny that the aisles only fit one person at a time. The shelves were stacked high, and you had to get a ladder to reach the top one. The books were ordered in sometimes surprising, but ultimately perfectly sensible ways. I remember the hours and hours spent browsing the shelves, looking for something I could read in my new, halting language.

I went back there last summer, for a visit, and was amazed that nothing had changed. The owner was there, and we chatted for a while about the old days. I know it sounds terribly cliché, but I would never have thought that some day my books would be sold there. (And I couldn’t have thought that not just because the idea of being published was so remote, but because back then I wasn’t even writing fiction in English yet.) The physical experience of browsing through a store—finding new, used, and even out-of-print books side by side—is one that I miss, particularly now that so many independent bookstores have closed.

A few weeks ago, when I heard that Farrar, Straus and Giroux was publishing a new volume of Mahmoud Darwish’s poetry, I was thrilled. But I was also a little disappointed that such recognition would come after his passing. (Darwish has been published in the United States before, of course, though never by a major commercial press.) The book is called If I Were Another, and it is translated by Fady Joudah.

“If I Were Another” (Farrar, Straus and Giroux) presents long poems from the latter part of Mr. Darwish’s career—the only part that the poet, persistently self-critical, regarded as “mature.” These “lyric epics,” drawn from four collections, weave together many settings and voices. An elegy for the author’s father is followed by a polyvocal poem spoken by birds; a series on Andalusia, by the monologue of a Native American.

You can read more on the book at Speakeasy, the WSJ‘s book blog. Joudah previously translated the lovely volume The Butterfly’s Burden, published by Copper Canyon Press.

I am in Indiana today, giving a talk at Notre Dame University. I don’t know if there are any readers of the blog in the area, but here are the details in case any of you are interested.

My trip over here was pleasantly uneventful, until the very end. A soldier who was returning home from Iraq was on the plane to South Bend. When we arrived, her little boy, no more than five or six, ran to greet her and wouldn’t let go. Everyone was staring. There wasn’t a dry eye in sight. I was happy to see her reunited with her family, but angered once again that she and so many others are fighting in this immoral, unjust war, which has brought only misery to the people of Iraq and the United States.