News

I spent a wonderful two weeks in Oregon, where I tried to stay away from the news and did little but hang out with friends, watch movies, and sleep. I did get a chance to read a few books, among which was a very good collection of essays, recommended to me by my friend Cristina. It’s called Notes from No Man’s Land by Eula Biss, and it explores the topic of race in America with refreshing honesty. Of course, it was impossible to stay away from the news after the foiled Christmas day attack on Northwest flight 253, the bombing of Yemen, and the open calls for strip searching all Muslim men between the ages of 18 and 28.

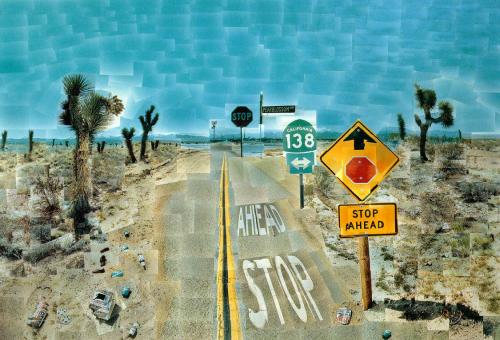

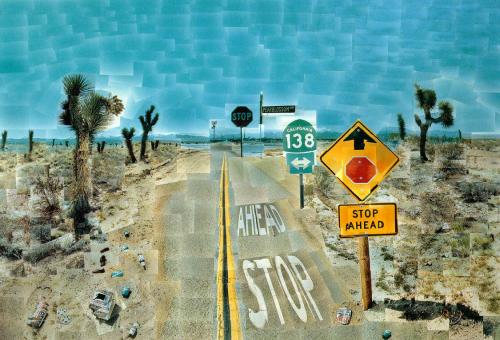

The picture above is a reproduction of Pearblossom Highway by David Hockney. The artist probably never meant for his collage of polaroids to be interpreted like this, but increasingly I feel that the world is like this little stretch of highway; one part is for people whose travel is restricted in all sorts of ways, and one part is for people who are free to move about as they want.

Yesterday marked the one-year anniversary of Israel’s air-, land- and sea-invasion of Gaza, which resulted in the loss of more than 1,400 lives. In Sunday’s Los Angeles Times, David Ulin reviews Joe Sacco’s long-awaited new book, Footnotes in Gaza, which is about a nearly forgotten massacre in in Rafah and Khan Younis. Here is a small excerpt:

Throughout the book, Sacco shows how much and how little things have changed by the use of what we might call time-fades: paired images that evoke a scene in the 1950s, followed by the same scene in the present day. The most striking of these comes at the climax of his account of the Khan Younis killings, in which he offers side-by-side illustrations, the first showing bodies piled against “the ruins of the 14th century castle, which now forms one side of the town square,” the second featuring the same castle half a century later, its walls festooned with handbills and graffiti, cars in a crowded row where the bodies once had been. Time marches on, Sacco means to tell us, and the past is only prologue if we pay attention to what it says. Yet even in a place so bound up by history, “[w]hat good would tending to history do . . . when [people] were under attack and their homes were being demolished now?”

You can read the review in full here. An excerpt from the book appeared on Mondoweiss this weekend.

Photo: Oregonian

In the most recent issue of the London Review of Books, Adam Shatz reviews Orhan Pamuk’s new novel, The Museum of Innocence, providing a more skeptical, cool-headed view of Pamuk’s work than what we’ve been accustomed to so far. Here is the opening paragraph:

Who could resist the charms, or doubt the importance, of a liberal, secular, Turkish Muslim writing formally adventurous, learned novels about the passionate collision of East and West? Orhan Pamuk is frequently described as a bridge between two great civilisations, and his major theme – the persistence of memory and tradition in Westernising, secular Turkey – is of a topicality, a significance, that it seems churlish to deny. His eight novels, the most recent of which, The Museum of Innocence, has just appeared in English, perform formal variations on that theme. Though his work fits into a Turkish tradition most closely associated with the mid-20th-century novelist Ahmet Tanpinar, one needn’t know anything about Tanpinar, or even about Turkish literature, to appreciate Pamuk, who writes in the Esperanto of international literary fiction, employing a playful postmodernism that freely mixes genres, from detective fiction to historical romance. Much of Pamuk’s fiction reads like a homage to his Western models: Mann, Faulkner, Borges, Joyce, Dostoevsky, Proust and – in The Museum of Innocence, the tale of a doomed, obsessional love affair between a man in his thirties and an 18-year-old shop girl – Nabokov. Indeed, his affection for the European tradition is as crucial to his appeal as his Turkishness, and his books pay tribute to values deeply embedded in the liberal imagination: romantic love freed from the fetters of tradition; individual creativity; freedom and tolerance; respect for difference.

You can read the piece, in its entirety, at the website of the London Review.

Photo credit: Martin Godwin/Guardian

I’m in Portland for a few days, to visit family and friends, and to relax until the start of the new year. I plan to spend most of today at Powell’s.

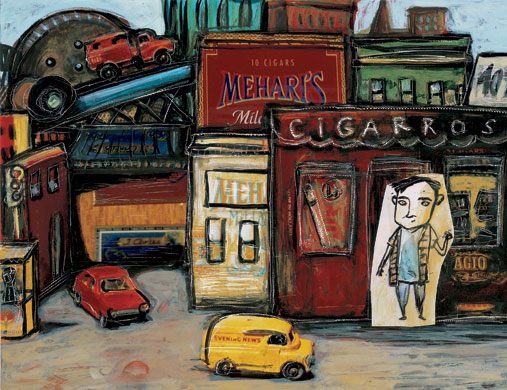

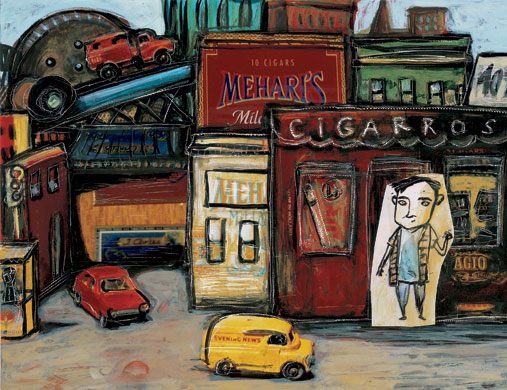

The Guardian has published a gallery of twelve beautiful pictures, which accompany a new edition of Paul Auster’s famed “Auggie Wren’s Christmas Story.” The story first appeared in the New York Times in 1990, and has been reprinted many times since. You can listen to Paul Auster read it on NPR. And of course the character of Auggie Wren appears in another Auster production, the film Smoke, which starred Harvey Keitel.

Illustration: ISOL/Faber and Faber