News

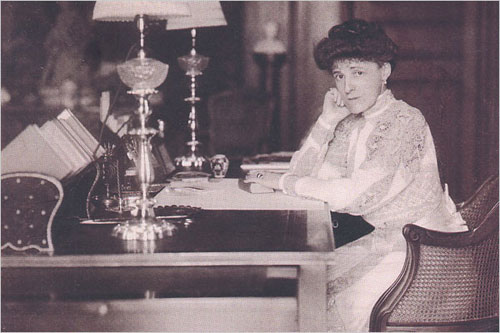

I am reading Edith Wharton’s travelogue In Morocco, which was published in 1920 (and which I believe has fallen out of print.) It is an amazing exemplar of what would later be called Orientalism–with musings about “Eastern laziness,” the “fatalism” of the people, the “grave clothes” that serve as attire, the “tortuous soul” of the land, and so on. A visit to the souk gives her the impression of “a draped, veiled, turbaned mob shrieking, bargaining, fist-shaking, calling on Allah to witness the monstrous villainies of the misbegotten miscreants they are trading with.” In contrast, she is full of praise for her host, General Lyautey (who served as Governor General) and his government. The French endeavor to keep the trails “fit for wheeled traffic,” they are “asked to intervene” to save antiquities, and at all times they show “respect for native habits [and] native beliefs.” What strikes me about these contrasts is not that they are outmoded, but rather the opposite: the same images, the same tropes are still to be found in travel writing or reportage about Morocco today. The book is turning up to be quite useful for a piece I’m doing on writing about Morocco (I know, I know, it’s very meta.)

Photo: Edith Wharton Restoration/New York Times

The passage below is the closing paragraph of “Harem,” by the Egyptian writer and academic Leila Ahmed. The essay is part of her magnificent memoir, Border Passage, and is about three generations of women in her family. It discusses the changes in their lives over a period of a century and a half.

If the women of my family were guilty of silence and acquiescence out of their inability to see past their own conditioning, I, too, have fallen in with notions instilled in me by my conditioning—and in ways that I did not even recognize until now, when, thinking about my foremothers, I suddenly saw in what I had myself just written my own unthinking collusion with the attitudes of the society in which I was raised. Writing of Aunt Farida and of how aggrieved and miserable she was when her husband took a second wife, I reproduced here without thinking the stories I’d heard as a youngster about how foolish Aunt Farida was, resorting to magic to bring back her husband. But I see now how those stories in effect rationalized and excused his conduct, implying that even though taking a second wife wasn’t a nice way for a man to behave, perhaps he had had some excuse, Aunt Farida being so foolish.

“The mind is so near itself,” Emily Dickinson wrote, “it cannot see distinctly.” Sometimes even the stories we ourselves tell dissolve before us as if a mist were momentarily lifting, and we glimpse in that instant our own participation in the myths and constructions of our societies.

The last time I used this essay in a class, a couple of my students appeared stunned to discover that there were feminists in Egypt, much less in 19th-century Egypt. Feminism (by which I mean simply the belief that men and women are and should be equal) had seemed to some of them, I think, primarily and uniquely a Western movement.

Photo: Harvard Gazette.

Yesterday I was talking about the fact that rejection is just a part of the writer’s life. Well, today I have the opportunity to mention another part of that life: the occasional (and, of course, fleeting) moment of recognition. The Orange Prize longlist for this year has been announced and I am happy to say that my novel, Secret Son, is included. The complete list of longlisted novels can be found on the website for the prize.

It seems I’ve been collecting rejection notices lately. Yesterday’s came from the MacDowell Colony, to which I had applied earlier this year because I wanted to get some writing done in a quiet place, away from home. I had visions of sitting in one of their cozy studios, sipping Earl Grey or Darjeeling or whatever, and composing my newest magnum opus. But that won’t be happening. I’m disappointed, of course, but over the last ten years I’ve learned that rejection is just part of the writer’s life. And I’ve also learned that you can’t really evaluate what a rejection means when it’s just happened; you have to wait to gain some perspective. I remember how disappointed I was to have a story rejected from a particular literary magazine, and now when I think about that I just laugh to myself because that magazine went out of business (and I ended publishing that story elsewhere anyway.) There’s a great book that I often recommend to my grad students when they get discouraged. It’s called Mortification: Writers’ Stories of their Public Shame. One of my favorites is the story that Margaret Atwood tells of giving a reading of The Edible Woman in the men’s sock and underwear section of a major department store.

Last week marked the end of the winter quarter at the University of California, which means I am finally able to take a little break. Actually, it’s a long break, since I am on leave in the spring quarter. I hope to finally have time to focus on my work and find a proper direction for the new book. I’ve been going through a tough time lately—not unhappy, but certainly fraught with all sorts of difficulties and familial worries—and of course it’s affected my work. I’ve been fortunate enough to receive the support of a few friends (and also disappointed in others, but that’s a story for another day.) There’s something about this new novel that’s very different. It takes place at a time and place I’ve never written about before, so there’s the challenge and excitement of that, and it also has an extremely important minor character, and I have to figure out how to do that well.