News

Thank you to all those who came to my panel discussion at the Casablanca Book Fair last week. (Or has it already been two weeks? I’m so tired I can’t think straight.) As usual, the fair was absolutely packed with publishers from all over Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East, as well as readers of all ages, including grade-school children. But, again as usual, the signage was poor, so it took me a little while to find the right booth. The event itself was a success, though, and I had a wonderful time.

I spent the rest of the week in Rabat, visiting family and catching up on news from the past year. Several friends have written me to ask what I think about the “political situation,” as the euphemism goes. I have to say I’m not very optimistic, given the economic downturn in Morocco and the continuing social discontent. But I’ll write in greater detail about all this very soon.

A quick post to let you know that I will be at the Casablanca Book Fair this Thursday. Here are the details:

February 16, 2012

5:40 PM

Ecrits d’Amérique

Stand du CCME

Salon du Livre

Rue Tiznit, Face à la Mosquée Hassan II

Casblanca, Morocco

If you are in the area, do stop by and say hello! (I am told the event will be in French.) I should also be at the Dar America booth at 3:30 pm, if you’d like to meet me and get your book signed.

In my last blog post, I talked about how I’ve been having a hard time with my new novel. I don’t like to complain about my novel–really, who needs more whining from a writer? But that week had been particularly brutal. Now, though, I’ve heard some lovely news, and I thought I’d share that with you too. I’ve been awarded a Lannan Residency Fellowship by the Lannan Foundation for next fall. What this means is that I will finally have that most precious of things: uninterrupted time to work on my book. The fellowship really could not have come at a better moment, so thank you to whoever nominated me for this!

I neglected to mention that, last month, the Guardian asked a few writers, including me, to reflect on the uprisings in the Arab world, one year later. And I also have an essay about Percival Everett’s new novel in this week’s Nation. (The article is only available to subscribers, but you can subscribe to the magazine here, for as little as $10.)

One last thing. Over the last few weeks, I’ve had to contend with several hacking attacks on my website. (As if I didn’t have enough craziness in my life.) So I’ve had to do a few upgrades to security, and I got myself a new design as well, thanks to the brilliant people at Being Wicked. If you’re looking for great web designers, hire them. They’re amazing.

I’ve just returned from Death Valley, where I went to decompress a bit after a particularly rough writing week. There’s something about the landscape there that resonates with me—it’s topographically diverse and incredibly peaceful. If you stand still for a moment, you can hear complete silence. Here is a picture of Titus Canyon early in the morning.

Farther down the trail in Titus Canyon:

Then there are the salt flats at Badwater Basin:

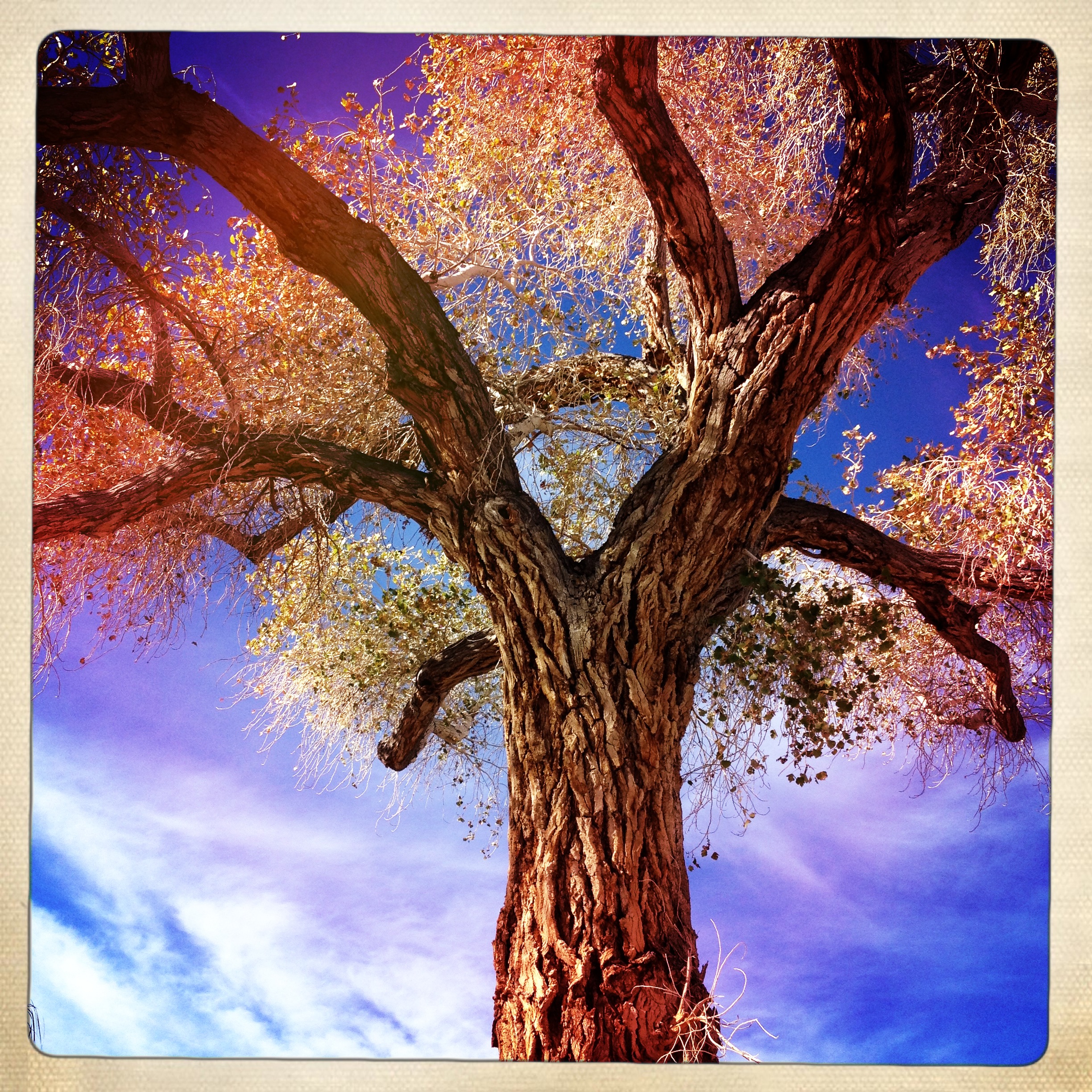

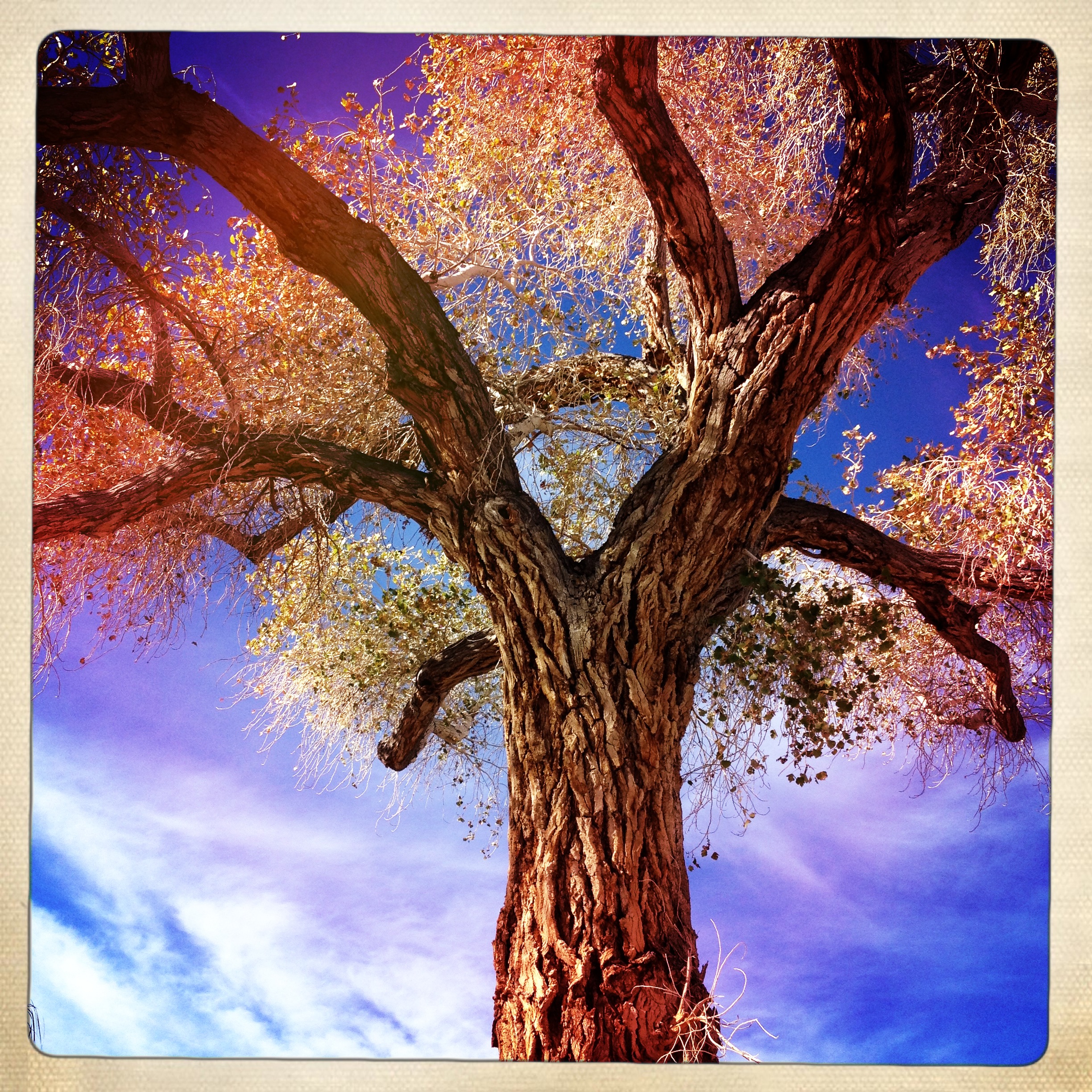

A cottonwood tree in Grapevine Canyon:

Ubehebe Crater:

And, lastly, Mustard Canyon:

Yesterday was the start of the winter quarter at UC, and, as a warm-up exercise for my first class, I used this writing prompt: “an affair has been discovered.” The point is to get students to think about who is telling the story (the cheater? the cheated-upon, the cheated-with?), the details of the discovery (how was the affair revealed? a nosey neighbor? a jealous husband?), the purpose of the story (is it a simple confession? a plea for forgiveness? a justification? a piece of gossip one character shares with another?), and its intended recipient (a priest? a divorce lawyer? one of the people involved in the affair?). These kinds of choices can have a significant effect on the shape of the narrative. A great example is Junot Díaz’s story “The Sun, The Moon, The Stars”:

I’m not a bad guy. I know how that sounds—defensive, unscrupulous—but it’s true. I’m like everybody else: weak, full of mistakes, but basically good. Magdalena disagrees. She considers me a typical Dominican man: a sucio, an asshole. See, many months ago, when Magda was still my girl, when I didn’t have to be careful about almost everything, I cheated on her with this chick who had tons of eighties freestyle hair. Didn’t tell Magda about it, either. You know how it is. A smelly bone like that, better off buried in the back yard of your life. Magda only found out because homegirl wrote her a fucking letter. And the letter had details. Shit you wouldn’t even tell your boys drunk.

The thing is, that particular bit of stupidity had been over for months. Me and Magda were on an upswing. We weren’t as distant as we’d been the winter I was cheating. The freeze was over. She was coming over to my place and instead of us hanging with my knucklehead boys—me smoking, her bored out of her skull—we were seeing movies. Driving out to different places to eat. Even caught a play at the Crossroads and I took her picture with some bigwig black playwrights, pictures where she’s seen smiling so much you’d think her wide-ass mouth was going to unhinge. We were a couple again. Visiting each other’s family on the weekends. Eating breakfast at diners hours before anybody else was up, rummaging through the New Brunswick library together, the one Carnegie built with his guilt money. A nice rhythm we had going. But then the Letter hits like a Star Trek grenade and detonates everything, past, present, future. Suddenly her folks want to kill me. It don’t matter that I helped them with their taxes two years running or that I mow their lawn. Her father, who used to treat me like his hijo, calls me an asshole on the phone. “You no deserve I speak to you in Spanish,” he says. I see one of Magda’s girlfriends at the Woodbridge Mall—Claribel, the ecuatoriana with the biology degree and the chinita eyes—and she treats me like I ate somebody’s kid.

You don’t even want to hear how it went down with Magda. Like a five-train collision. She threw Cassandra’s letter at me—it missed and landed under a Volvo—and then she sat down on the curb and started hyperventilating. “Oh, God,” she wailed. “Oh, my God.”

This is when boys claim they would have pulled a Total Fucking Denial. Cassandra who? I was too sick to my stomach even to try. I sat down next to her, grabbed her flailing arms, and said some dumb shit like “You have to listen to me, Magda. Or you won’t understand.”

Here, the narrator begins with a pre-emptive defense (“I’m not a bad guy”). But he is aware that this defense itself might be incriminating (“I know how that sounds”), so he provides some justification for his actions as well (“I’m weak.” “I”m like everybody else.”) Then he gives his girlfriend’s opinion, which he ties to a stereotypical view of all Dominican men—a clever way of giving us Magdalena’s side of the story while also retaining our sympathy. This very delicate balance is maintained for the remainder of the story, when the narrator, Yunior, takes Magdalena with him to Santo Domingo, where they try to patch up their relationship and where, of course, nothing goes as planned.

The story originally appeared in The New Yorker and was anthologized in Best American Stories 1999.

Photo credit: Blogamole.