News

My new novel, The Moor’s Account, comes out today. The journey from conception to publication has been long, but it has been wonderful in every way. I’m very proud of this book and I hope you enjoy reading it. I’m also thrilled to see that it has already received some notice. For instance, in its review, The New York Times called it “a fictional memoir told in a controlled voice that feels at once historical and contemporary.” The Los Angeles Times said it was a “rich novel (…) that muses on the ambiguous power of words to either tell the truth or reshape it according to our desires.” Other reviews and mentions appeared in BookPage, The Huffington Post, and The Village Voice. And you can hear me discuss the novel with Arun Rath on NPR’s All Things Considered.

I will be launching The Moor’s Account in Los Angeles this week, at two separate events. Tomorrow, I’ll read from and discuss it at Skylight:

September 10, 2014

7:30 PM

Reading and Discussion

Skylight Books

1818 N Vermont Ave.

Los Angeles, California

And then this Sunday, I’ll be speaking at Diesel in Brentwood. Details are below:

September 14, 2014

3:00 PM

Reading and Discussion

Diesel, A Bookstore

Brentwood Country Mart

225 26th Street, Ste. 33.

Brentwood, California

After that, I will be going on a huge tour to promote the book. All my scheduled readings are posted on my Events page. Do come.

In trying to make sense of the injustice and the violence that has been unfolding in Ferguson for the last couple of weeks, I returned to James Baldwin’s essay “Notes of a Native Son,” and recommended it for NPR’s All Things Considered.

It is early August. A black man is shot by a white policeman. And the effect on the community is of “a lit match in a tin of gasoline.” No, this is not Ferguson, Mo. This was Harlem in August 1943, a period that James Baldwin writes about in the essay that gives its title to his seminal collection, Notes of a Native Son.

You can listen to the piece on NPR’s website.

Photo: Robert Cohen/St. Louis Post-Dispatch/AP. A demonstrator throws back a tear gas container after tactical officers worked to break up a group of bystanders on Chambers Road and West Florissant, Aug. 13, 2014, in St. Louis.

Book tours sound very glamorous, but they usually go like this: you wake up at an ungodly hour, you hope that your cab is on time, you hope that your flight is on time, you hope that your seat mate isn’t a sociopath, you hope that your hotel room is ready when you get there, you hope not to get lost on your way to the bookstore. All that hoping can be stressful. So why go on tour? Because after a few years of writing a novel, it’s very enjoyable to talk to readers about it. I have the most amazing readers. Once, at a reading in Los Angeles, a woman told me she had driven three hours so her daughter could come see me. Another time, my friend A. from grad school surprised me by showing up at my Elliott Bay reading in Seattle. He lives in Arizona, but was in town on business, so we ended up having dinner together and catching up. And I love doing events in independent bookstores because, unfailingly, the staff are knowledgeable, friendly, and always have a good book to recommend. Yes, book tours are stressful, but they’re also lots of fun. Right now, I’m getting ready to tour for my new novel, The Moor’s Account. I’ll be visiting Los Angeles, Seattle, San Francisco, Portland, Albuquerque, Santa Fe, New York, Washington DC, and Boston this fall. I’m also doing the Chicago Humanities Festival, the International Festival of Authors in Toronto, and the Miami Book Fair. And I’m speaking at several colleges, including Williams in Massachusetts, Yavapai College in Arizona, and the University of Texas at Austin. Do come by and say hello! I’d love to talk to you about my new book.

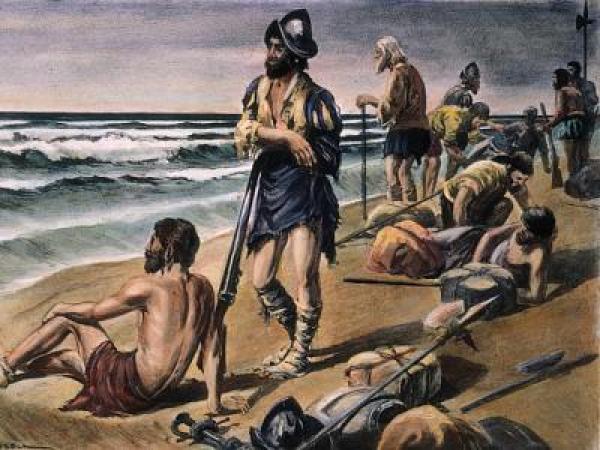

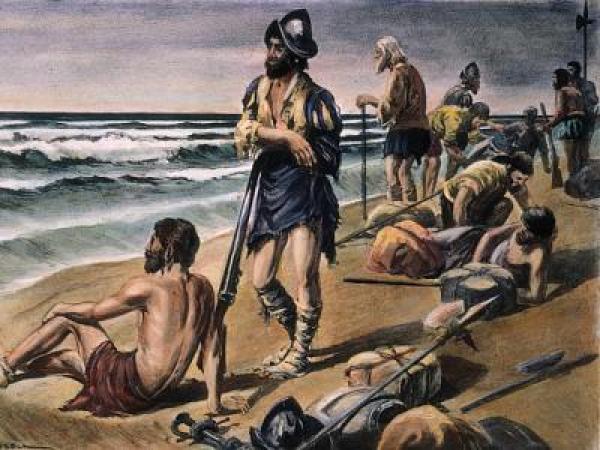

While writing The Moor’s Account, I became curious about visual representations of Estebanico (a.k.a. Mustafa al-Zamori). As it turned out, the incredible story of the Narváez expedition inspired quite a few painters. Below, for instance, is the depiction of the Narváez castaways that Penguin Classics used for its cover of Cabeza de Vaca’s Chronicle. You will notice that Estebanico appears nowhere in it.

But as time passed and scholarship evolved, interest in Estebanico also grew. Here is a painting by José Cisneros, where Estebanico appears alongside the other three survivors, Andrés Dorantes, Alonso del Castillo, and Cabeza de Vaca. (Estebanico is second from right.)

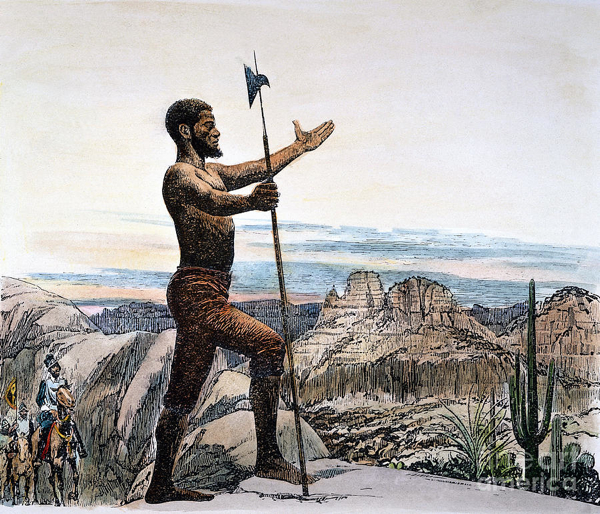

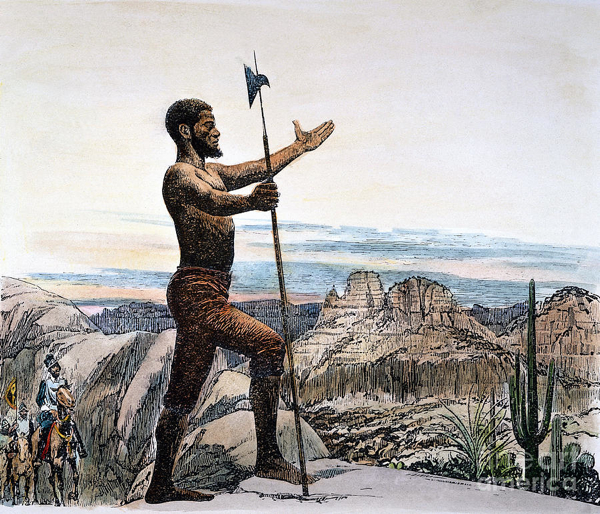

It’s interesting to note the differences between artist depictions when it comes to style and dress. In the one below, for example, Estebanico appears shirtless and carrying a halberd, leading the way for the Coronado expedition, which took place many years after the Narváez expedition.

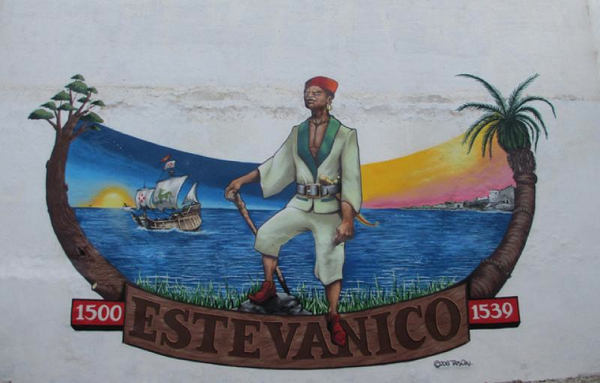

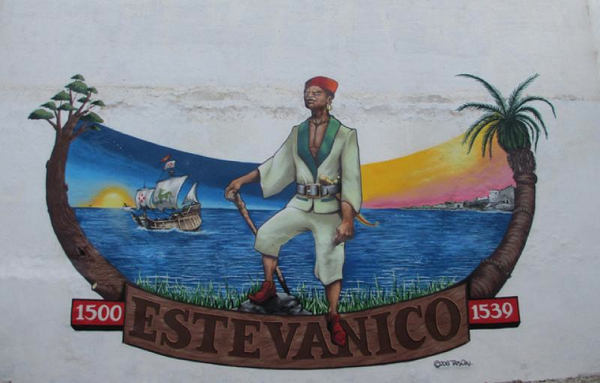

In his hometown of Azemmur, there are a few murals dedicated to the explorer. Here is one where Estebanico is portrayed in the dress and style of a pirate. (Of course, he was no pirate; he was a slave turned scout turned faith healer.)

Adjacent to that mural in Azemmur is another one, also depicting Estebanico. Here, the explorer is shown wearing a turban and a loincloth, and carrying a wooden lance.

What I find fascinating about all these images is what they tell us not about Estebanico, but about the artists themselves. Each one had a different view of the explorer, shaped by his or her culture and experience of history.

Image credits:

1. Alfred Russell, Alvar Nuñez Cabeza de Vaca and His Companions Lost on the Shore of the Gulf of Mexico, 1528. The Granger Collection. New York.

2. José Cisneros, Cabeza de Vaca and His Three companions on the Texas Coast. Museum of South Texas History.

3. Artist unknown, Estevanico. The Granger Collection. New York.

4. Artist name illegible, Estevanico/Estebanico El Azemmouri. MonMaroc Guide.

5. Koukou. Estebanico. Azemmur.

My new novel, The Moor’s Account, comes out in five weeks. It tells the story of America’s first African explorer, a Moroccan slave known as Estebanico. He was part of the Narváez expedition of 1528, which landed in Florida with the goal of claiming it for the Spanish Crown. From the start, however, the expedition faced disaster. The rations were small, the men came down with typhoid, and the indigenous tribes resisted the soldiers’ advance. Within a year, there were only four survivors: the expedition’s treasurer, Cabeza de Vaca; a captain by the name of Alonso del Castillo; a nobleman named Andrés Dorantes, and his Moroccan slave, Estebanico. Together, the survivors journeyed across America, living with native tribes and reinventing themselves as faith healers. Years later, when they were found, the Spaniards were asked to provide their testimony about this epic journey. But because he was a slave, Estebanico’s experience was considered irrelevant or unreliable or unworthy.

And yet his experience was unique. Although he took part in a conquering expedition, he was not a conqueror. He witnessed the Spaniards’ subjugation of indigenous tribes, while his own status was somewhere in between. The complexity of Estebanico’s position drew me in, as did the fact that his testimony was not part of the historical record. The silencing of his perspective felt modern to me. (Open up the newspaper and look at the bylines. Whose views do you read? Whose voices do you never hear?) I was so immediately and so powerfully drawn to Estebanico’s story that I decided to write a novel about him. I gave myself the freedom to speak in his voice, to describe his birth in Azemmur, his family life, his relationships with others, his many failings, and ultimately his redemption.

Last month, I had the chance to return to Azemmur. In the picture above, I’m standing where, I imagine, he once stood. To my right are the Portuguese ramparts, which date back to 1513; the Oum er-Rbi’ river is to my left.