Month: November 2009

From the title story in Tim O’Brien’s The Things They Carried:

First Lieutenant Jimmy Cross carried letters from a girl named Martha, a junior at Mount Sebastian College in New Jersey. They were not love letters, but Lieutenant Cross was hoping, so he kept them folded in plastic at the bottom of his rucksack. In the late afternoon, after a day’s march, he would dig his foxhole, wash his hands under a canteen, unwrap the letters, hold them with the tips of his fingers, and spend the last hour of fight pretending. He would imagine romantic camping trips into the White Mountains in New Hampshire. He would sometimes taste the envelope flaps, knowing her tongue had been there. More than anything, he wanted Martha to love him as he loved her, but the letters were mostly chatty, elusive on the matter of love. She was a virgin, he was almost sure. She was an English major at Mount Sebastian, and she wrote beautifully about her professors and roommates and midterm exams, about her respect for Chaucer and her great affection for Virginia Woolf. She often quoted lines of poetry; she never mentioned the war, except to say, Jimmy, take care of yourself. The letters weighed ten ounces. They were signed “Love, Martha,” but Lieutenant Cross understood that Love was only a way of signing and did not mean what he sometimes pretended it meant. At dusk, he would carefully return the letters to his rucksack. Slowly, a bit distracted, he would get up and move among his men, checking the perimeter, then at full dark he would return to his hole and watch the night and wonder if Martha was a virgin.

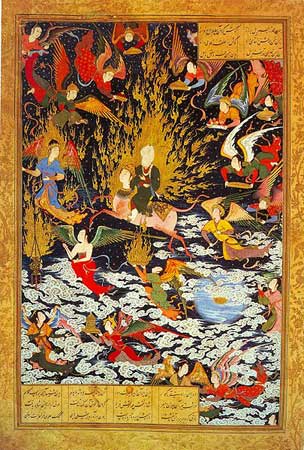

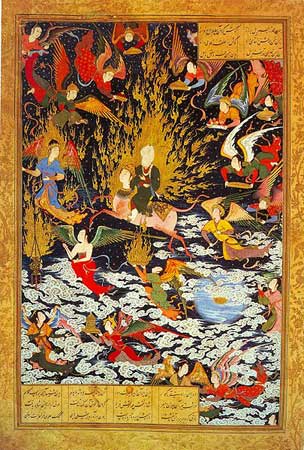

Last month, the scholar Jytte Klausen published a book on the controversy surrounding the Jyllands-Posten caricatures of the Prophet Muhammad. But, despite its title, The Cartoons That Shook The World didn’t include any images. Yale University Press, Klausen’s publisher, decided to censor the cartoons out of fear that they could lead to trouble here in the United States. Of course, that only led to more controversy. (For the record, I happen to think Yale should have included the images, because they are crucial for any full understanding of the situation. To exclude them makes a thorough discussion impossible.)

In the New Republic, Oleg Grabar examines the larger question of representations of the Prophet Muhammad. He takes the reader on a little history tour through Islamic art. For instance, he discusses various representations of the Prophet Muhammad in printed form, particularly in depictions of Isra’ and Mi’raj (the mythical Night Journey, as in the image above). Although I am not entirely comfortable with claims he makes about “the Muslim world,” it is hard to take any issue with his conclusion:

To the extent that the argument against the so-called cartoons has centered on the legal propriety or impropriety of representing the Prophet Muhammad, it has been a pointless argument. Of course it is possible to question the Danish caricatures on grounds of taste, or social or political intent; but the lack of taste is not a legal category, and mischievous or even evil intent is difficult to discern in the absence of clearly stated moral and philosophical principles. The only certain lesson to draw from the sad story of the Danish cartoons is the almost universal prevalence of ignorance and incompetence–and that everyone, from writers and pundits to the leaders of mobs, should learn more before making a judgment or starting a riot.

You can read the essay in full here.

The Zimbabwean writer Petina Gappah (whose debut story collection, An Elegy for Easterly, came out a few months ago) has some excellent advice for young writers on her blog. She writes:

A lot more people just want to know how they can be “real” , and that word keeps coming up, how they can be “real” writers. It is to these aspiring writers that I now reveal the secret to writing success.

Write.

That’s it.

Just write.

A writer is a person who writes.

Talent is overrated. Luck is overrated. The right agent is overrated. It helps to have all three, but they are all worthless without that thing in your hand, the manuscript, the thing in your hand that may become a book for which trees will die and that will be published and primped and pampered and put on bookshelves and paid for by people.

And this is what is underrated: the sitting down and grinding it out part. Because that is what writing is. You, at your computer or with your notebook, writing, and writing, revising and writing, and revising again.

This resonated with me because earlier this week, a student asked me for some career advice. I wasn’t sure what exactly she meant, and when I inquired it turned out she was very anxious because she felt that she should “put herself out there” and “try to get published.” She said that I was the only professor she had who never discussed publication or career in class. So she was curious. I told her that I didn’t discuss publication because I felt that the class should be spent on writing. I asked her how many stories she had written. The answer was: not very many. And so my advice to her was to write. I think I will also tell her to read what Gappah wrote.

When I went to see Chris Rock’s documentary, Good Hair, the other day, it got me thinking about how curly hair is written about in novels. The first example that came to me was Philip Roth’s The Human Stain. In the novel, Coleman Silk describes Iris Gittelman, the woman he’s going to marry, mostly in terms of her hair:

Her head of hair was something, a labyrinthine, billowing wreath of spirals and ringlets, fuzzy as twine and large enough for use as a Christmas ornamentation. All the disquiet of her childhood seemed to have passed into the convolutions of her sinuous thicket of hair. Her irreversible hair. You could polish pots with it and no more alter its construction than if it were harvested from the inky depths of the sea, some kind of wiry, reef-building organism, a dense living onyx hybrid of coral and shrubs, perhaps possessing medicinal properties.

Iris’s hair is significant, of course. Its curative property, so to speak, is that it allows Coleman, who has been passing for white, to have a convenient explanation for any kinkiness in his children’s hair.